Accepting the 2001 Sydney Peace Prize, Sir William Deane, former High Court Justice and Australian Governor General, delivered a lecture on ‘The Search for Aboriginal Reconciliation.’

In it he remarked:

[The] oppression and injustice to which indigenous Australians were subjected in our land and under our Federation were not merely the acts of individuals who are long since dead and for whose acts living Australians might deny responsibility. They are properly to be seen as acts of the nation itself of which all living Australians are members. As such, that past oppression and injustice remains part of the very fabric of our country. They reach from the past to blight the present and to demand redress and reconciliation in the future.

Subscription to these views is commonplace and widely considered to be ‘progressive’.

Since the early 1990s, one wing of the Australian ruling elite, having embraced such pieties as useful to its interests, has encouraged their diffusion throughout public opinion under the banner of ‘reconciliation’.

Journalists and academics, apt to take their cue from official sources, have typically followed.

Socially respectable, this conventional wisdom is now promoted by left-liberal organizations like the Sydney Peace Foundation as a necessary part of acknowledging and helping to repair the awesome genocidal catastrophe of Australia’s European colonization.

For much of Australia’s broader non-Indigenous population, stirred by genuine sympathy for the injustices and depredations inflicted on Indigenous people, illusions persist about the purpose of what is presented to them as a kind of national atonement.

The country’s political establishment, for reasons of expedience, promotes collective expiation as a way to ‘heal wounds’ and allow ‘new partnerships’. Editors and executives have approved the project as a matter of ideological etiquette and table manners.

But Deane’s lofty notion of collective guilt — underpinned by a vision of ‘the nation’ as a collective moral agent, a persona ficta capable of undertaking actions and bearing culpability for them — has an unpleasant heritage, questionable logic and reactionary political implications.

Let me explain what I mean, since to say all this is to reverse the evaluative claims typically made for these ideas by the state, the media and intelligentsia. Questioning the political packaging in which such ideas are draped, and the aisle and shelf in which they have been placed in the ideological supermarket, is bound to be jarring.

Many politically conservative people also reject statements like Deane’s above, and for bad reasons. Wary readers may fear that I will present similar arguments here. They may even believe that someone rejecting views like Deane’s is thereby somehow obliged to endorse some right-wing belief or sentiments. Or they may think that any criticism lends succour to the political Right or is strategically unwise for those with politically opposite views (e.g. because it lessens the confidence of the enemies of the political Right).

But I think that the opposite is true. I believe that views like Deane’s — the idea of ‘national responsibility’ for one of history’s great crimes, ‘the oppression and injustice to which indigenous Australians were subjected’ — are inconsistent with the cause of understanding and addressing the evils of settler colonialism. Affirming them, far from encouraging ‘redress’ of the consequences of that crime, hinders it.

We therefore can (and indeed should) reject such views for reasons independent of the reasons that political conservatives deny them. And we can relax from fears that we are being counterproductive or unwittingly advancing the aims of the political Right.

What does it mean to speak, as Deane does, of inherited responsibility for ‘acts of the nation itself of which all living Australians are members’?

Firstly, his claim that guilt is laterally transferred — i.e. that a supra-individual entity or group (an entire nation, race, gender, etc.) is responsible for the behaviour of the member individuals who make it up — is accompanied, as usual, with the pendant idea that this group liability is transmitted vertically across generations, a mortmain of culpability (‘Let his blood be upon us, and on our children’).

The latter has been a traditionally toxic formulation wherever it has been introduced.

Yet maybe there is nothing wrong with the notion, so long as it is applied properly — say, to a genuinely powerful group, rather than an oppressed minority. Its dubious precursors aside, is there any sense to the idea? Does it capture something about settler colonialism that other critical accounts of Australian history neglect?

Let’s run through the ideological vision as it’s propounded by official sources such as Deane.

In Australia, as with the biblical case of ‘collective guilt’, causal responsibility for the wrongful deeds is acknowledged to lie with specific historical agents, natural persons who may be named and arraigned: individuals and entities including colonial administrators, military officers and police, pastoralists, ‘gentleman settlers’, magistrates, civil servants, Chief Protectors, missionaries and miners, having acted both singly and in concert.

But surely all these people and organizations were not working independently of each other, in separate enterprises that did not in some sense cohere into a larger shared project of colonization. So, in the Australian case as elsewhere, an additional degree of moral blame (culpability) is attributed to a macro-agent: conceived of as a particular identity group, whose members share the same (putative) racial, ethnic or national identity as the direct perpetrators.

For the group is believed to constitute a kind of supra-individual personality (a reified ‘white people’, ‘the Jews’ or ‘the nation’), capable of having beliefs, pursuing goals and undertaking actions.

The collective identity of this group is held to persist across time, despite changes in personnel. It has a ‘general will’, which is something more than (i.e. can’t be reduced or decomposed to) a mere aggregation of individual wills. Like a limited liability company (rather than a partnership), it survives the departure of those specific individuals who bear the stain of direct causal responsibility.

Indeed, it’s possible to see the action for which blame was incurred as having somehow been undertaken by the collective entity.

The apportionment of culpability to the responsible individuals thus doesn’t exhaust things: a residue of guilt must be attributed to the supra-individual entity itself (‘vicarious liability’), and thus to all individuals who constitute it.

Guilt thereafter accrues to later-arriving members of the collective personality, i.e., individuals who possess the attributes by which group membership is defined. A kind of metaphysical guilt thus ‘reaches from the past’ down to members of subsequent generations. So long as the putative ‘nation’ or ‘race’ endures, and until the liability is discharged, the guilt of its members is undying.

Guilt for ‘what he or she has done to others’ thus taints each person descended from the perpetrators of ‘white aggression and racism’. On Sorry Day, and in Sorry Books, non-Indigenous people are invited to imagine themseves as ‘white’, then to express contrition for the past behaviour of fellow ‘white people’.

Of course, the völkisch basis of inherited responsibility may be downplayed.

In such cases, it won’t be claimed that a nation or race is the type of foresightful, purposeful collective actor that can do something, such as commit a moral wrong. But it’s held that such an act can be performed on its behalf (i.e. to its collective advantage), so that its members thereby incur a debt or degree of culpability.

Thus, for the ANU historian Ann Curthoys, all non-Indigenous Australians today bear guilt as ‘the beneficiaries of the colonisation process’.

But cui bono? is, to say the least, an unorthodox way to determine moral responsibility (the awful Susan Brownmiller is a rare proponent of the idea). Culpability for some harm inflicted on another isn’t usually thought to follow from the mere fact of having benefited, ex post, from that injurious act or occurrence.

That aside, Curthoys leaves unargued exactly how the entire non-Indigenous population — rather than some small subset of it — has benefited from the devastation of Indigenous Australian societies.

Do Deane and Curthoys not bestow a curious anonymity on the political agents responsible for these sinister deeds, and disguise the purpose of their enterprise? Is the villain of the piece, ‘the nation’, or ‘white people’, not a pure abstraction?

More importantly and troublingly, the upshot of Curthoys’s claim that ‘all migrants and their descendants’ have ‘benefited from colonisation’ is that Australian history (and current political circumstances) must be understood simultaneously as a zero-sum conflict between Indigenous and non-Indigenous groups and a harmonious ‘common-interest game’ within each respective group.

That is to say, on Curthoys’s vision the two ethnic groups have contended over relative shares of some pie. More for one group has meant more for all members of that group and less for all members of the other group.

Thus conflicts of interest within groups are entirely absent, while pure conflict exists between groups: the fortunes of members of one group (Indigenous Australians) vary inversely with the welfare of all other people.

The political implication of this argument is dire and reactionary: if A benefits by inflicting some loss on B, then B can only gain or recover the loss at A’s expense, in which case A isn’t a credible ally for any project by B to advance its material interests, for in doing so A would be harming itself.

B can only satisfy its wants by breaking with A; or as Thomas Schelling explained:

[In a] common-interest game we can refer to [the players] as ‘partners’ and in the pure-conflict game as ‘opponents’ or ‘adversaries.’

The spread of such beliefs upholds the political exclusivity of groups defined along ethnic (or linguistic, religious etc.) lines. It partitions members of populations who otherwise might act in political concert, while suppressing other salient social distinctions (e.g. class) that might otherwise lead to political divisions.

The prospect of working-class unity is thereby neutralized, and this surely is one reason why Australia’s political elite has found promotion of these ideas to be expedient.

Of course, this doesn’t speak to the truth of Curthoys’s factual claim. Whether or not it’s to be preferred shouldn’t be decided on the grounds of political handicap or usefulness, but on whether or not it provides a true description of historical events.

Like the children’s messages scrawled in the Sorry Book above, the portrayal of Deane and Curthoys obscures the actual causal process of settler colonialism.

The Australian genocide, in its initial high-impact decades, involved the British state assuming radical title over fertile land, then distributing it and other assets to graziers and farmers. This seizure and re-allocation of resources was enforced through direct violence (by the state and by private agents of the new owners).

More crucially, the creation of possession-based property rights over economic resources entailed the denial (in the name of the owner’s exclusive dominion) of access and use by non-owners to their hitherto secure means of livelihood: hunting grounds, watering holes and shelter. That ousting dealt a massive shock to previously stable practices of subsistence acquisition and societal reproduction.

Worldly things and domains that formerly were open-access were suddenly no longer available for non-owners to satisfy basic needs, undertake sustenance-drawing activities or secure personal livelihoods.

Disruption to the existing regime of self-provisioning, sharing and related types of food production produced a sudden reliance for material subsistence on wage income, market exchange, charity or other novel transactions. This in turn disrupted the kinship practices and forms of cultural transmission that governed pre-colonial Australian societies.

Colonial authorities (and their successors) then attempted, in the manner of war victors, to eradicate the cultures, behavioural patterns and child-rearing practices of the defeated forager societies, and to replace them with norms and preferences more suited to the new market-based economy.

High fatality rates followed exposure to new disease environments. The latter arose through (i) the creation of high-density settlements in what formerly were sparsely populated areas, (ii) population displacement through inter-regional labour markets, and (iii) the introduction of alien pathogens by the colonizers.

Together with disruption of kinship systems and breaking apart of social units, this led to imbalanced sex ratios: changed sexual practices then encouraged the spread of venereal diseases, which led to a sharp and prolonged fall in fertility.

Such catastrophic social disruption then produced the sort of dysfunctional behaviour displayed regularly, over the past five centuries, by peoples defeated by capitalist imperialism: alcoholism, prostitution and high rates of interpersonal violence.

Of course, the displacement of one society by another carrying a novel set of institutions (involving, among other things, catastrophic demographic decline in the original population, and mass export of a new settler population) is something very different from a simple on-off event (say, a crime committed by an individual person). A process on this scale, to the extent that it involved deliberate design, required the coordination of many diverse participants into institutional collectivities (corporate bodies like civil service departments, military units, business firms, clubs and political organizations).

In these collective entities, group solidarity and a sense of common purpose were regularly maintained by appeals to a shared European ancestry. Ethnic stratification, rather than class membership, often was the ideological basis for distinguishing insiders from outsiders.

But it’s quite a step from acknowledging this to suggesting (as today’s socially sanctioned authority figures and cultural models obviously have done to the children writing above) that colonization (and post-Federation rule) was somehow an expression of the ‘general will’ of ‘white people’ or ‘the nation’.

The ways in which historical actors (sometimes) described, legitimized or understood their own activities ought not to govern our understanding of those activities today.

Historian Marilyn Lake has said:

Aboriginal people were active in identifying all settlers – whether hut-keepers, clergymen, convicts or military officers – as one people, as ‘white men’, whom they held jointly responsible for taking their land… [The indiscriminate nature of] Aboriginal retaliation and revenge… is explained by the Aboriginal perception that a group of people defined by their ‘whiteness’ had taken their country.

Supposing this was in fact ‘the Aboriginal perception’, it was a mistaken and regrettable (though entirely understandable) one. The tangible resources of Australia were seized by, and property rights in them apportioned to, a very small group of people, all of whom had European ancestry.

But none of these property holders could sensibly be defined by their ancestry, since the vast majority of ‘white men’ did not (as today most non-Indigenous Australians do not) own productive assets.

In this respect, the concentrated pattern of landholding that emerged during the mid-19th century in the Australian colonies may be distinguished from that which resulted from the Ottoman genocide of Armenians during the First World War.

In the latter case, title deeds to plundered Armenian estates, farms, workshops, factories, orchards and vineyards were allocated broadly to the Anatolian peasantry.

In the eastern Australian colonies, no such egalitarian smallholding grew up on the land confiscated from its displaced and hunted Indigenous inhabitants.

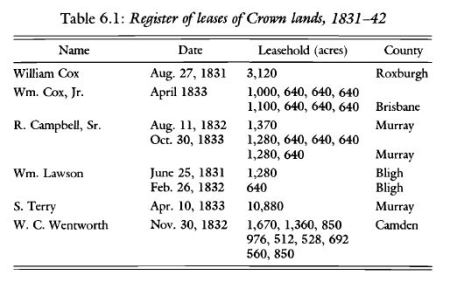

In the initial decades following British settlement, land grants were dispensed to military officers and other favoured clients of the governor. Later, from the 1830s, this narrow patronage system was replaced by land sales along Wakefieldian lines, designed to guarantee a supply of labour to capitalist employers.

The ‘sole object’ of a land price, declared Wakefield, was ‘to prevent labourers from turning into landowners.’

Cultivable or grazing land was henceforth accessible only to the wealthy and creditworthy. In 1851, 31 million acres of the Port Phillip District were held by fewer than 1000 squatting licence-holders.

Ownership was further consolidated as the nineteenth century progressed.

The picture of ‘white’ yeomanry dotting the Australian continent, although a powerful ideological symbol, was nothing more than an image d’Épinal. From the outset colonial New South Wales was an urban society, not a peasant one.

Secondly, with regard to Lake’s claim, the ‘collective actors’ responsible for colonization were exclusive institutions which left almost no room for popular participation.

During the first 70 years of their existence, the Australian colonies concentrated decision-making authority in a tiny number of people. For four decades after settlement New South Wales was a military dictatorship (what Bayly called the ‘proconsular despotism’ common throughout the Empire between Pitt and the Reform Bill). For the next 30 years, autocratic rule was broadened to include an oligarchic elite, allowing the voice of special interests, especially graziers and merchants, to be heard.

Thereafter, the formation of representative assemblies and broadening of the franchise made elite decisionmaking only weakly accountable to the vast majority of the settler population: members of the subordinate and asset-free classes. And by this time (indeed, even by the 1830s), many of the most consequential decisions concerning the fundamentals of Australian life (where economic activity would occur, and how, etc.) were made by powerful private actors (pastoralists and banks) whose property rights kept their decisions beyond the reach of democratic accountability.

Thirdly, while the devastation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander societies did require the decentralized action of many people from various economic classes (i.e. something broader than a narrow elite coalition), this didn’t involve the deliberate pursuit, in unison by all settlers of European ancestry, of shared goals.

It did, however, involve the (unplanned) coordination of these individuals, via a set of rules, institutions, constraints and incentives which governed how the members of colonial Australian society interacted and behaved, such that social development was channelled in a particular terrible direction.

This set of durable rules governing Australian society was not decided by the broad population in any electoral vote or constitutional convention. Nor were many of the institutions spontaneously accreted over decades. They were laid out purposely in royal charters and letters patent, and in strategic documents like the Bigge reports.

How did this work?

There were, as there are in each society, a set of economic institutions and social relationships governing how individuals could acquire a livelihood (i.e. what they had to do or be to acquire the goods and services needed to survive).

Thus Australian forager societies, before the arrival of British colonizers, involved customary rules of sharing and division, norms which Indigenous populations struggled to maintain subsequently, as described above. These rules then constrained who interacted with whom, the terms on which they met, the rights and obligations of each party to the transaction, etc.

And, in colonial Australia as in any society, the most important of these rules (those defining the set of feasible actions available to individuals and the payoffs attached to them) were the definition of property rights in economic resources, and their allocation to particular individuals, and the contracts (i.e. the type of social relationships) available to people given their level of wealth.

By virtue of (above all) what resources they did or didn’t possess, members of the various classes that made up post-1788 Australian society were compelled to act in particular ways, prevented from behaving in certain other ways, or otherwise had incentives which predisposed them to do some things and not others. This was what Jon Elster called ‘endowment-generated behaviour.’

But today’s ‘progressive’ opinion cannot confront these matters, for to seriously investigate the historical record would lead to undesirable political conclusions. Thus Sorry Day and its backers discourage anyone from inquiring into the social relationships underlying the devastation inflicted on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island people.

Yet lapidary and insightful description of this genocidal process does exist.

It can be found, for example, in the work of Rosa Luxemburg, who wrote in 1913 of how ‘modern colonial policy’ seized ‘the land, its hidden mineral treasure, and its meadows, woods and water, and further the flocks of the primitive shepherd tribes’ that occupied ‘vast tracts of the globe’s surface’ outside Europe:

Since the primitive associations of the natives are the strongest protection for their social organizations and for their material bases of existence, capital must begin by planning for the systematic destruction and annihilation of all the non-capitalist social units which obstruct its development…

From the point of view of the primitive societies involved, it is a matter of life or death; for them there can be no other attitude than opposition and fight to the finish – complete exhaustion and extinction. Hence permanent occupation of the colonies by the military, native risings and punitive expeditions are the order of the day for any colonial regime. The method of violence, then, is the immediate consequence of the clash between capitalism and the organizations of a natural economy which would restrict accumulation.

This, written 100 years ago in Europe, is a vastly more accurate, devastating and useful account of the criminal policy behind the Australian genocide than the pious self-mortification about ‘acts of the nation’ promoted today by the Sydney Peace Foundation and other progressives.

By scattering historical focus away from the collective action of propertyholders and state elites (and away from the institutional evolution they begat), and towards a putative ‘white people’, the account of Deane, Lake and Curthoys harmlessly distributes the guilt of perpetrators across time, till both all and none are to blame. And, as Deane says, without understanding liability, it’s impossible to propose an appropriate remedy.

Curthoys does, however, make a useful contribution. This is to suggest that the ‘black armband’ and ‘white blindfold’ historians are two sides of the same coin.

For both groups, the central problem of Australian historiography is the moral status of ‘white’ people:

Looked at more closely, the contest over the past is perhaps not between positive and negative versions, but between those which place white Australians as victims, struggling heroically against adversity, and those which place them as aggressors and perpetrators, bringing adversity upon others.

Curthoys’s predictable stance is that both positions are, in a sense, true: at least both are ‘narratives, stories about the past which make sense to those who tell and receive them.’ A more useful response, surely, is that both versions are false.

It is not as moral melodrama, in which ‘white’ and non-white Australians contest, that the awful episodes of colonial history are best organized and understood. Instead something like Luxemburg’s version does much better, both as description and analysis of the facts, and as basis for political action.

Tags: Aboriginal Australians, Ann Curthoys, collective guilt, compensatory justice, identity politics, Indigenous Australians, nationalism, Sorry Day

May 31, 2010 at 3:22 pm |

I agree with you on certain points (particularly this: “By scattering historical focus away from these propertyholders and state elites, and towards a putative “white people”, Curthoys’s account harmlessly distributes the guilt of perpetrators across time, till both all and none are to blame”), but on the whole I disagree. The biggest problem is that I think you’re setting up a bit of a straw man of Sorry Day (“non-Indigenous people are invited to imagine themseves as ‘white’,” – invited? By who?). Anyway, here are a few disconnected points.

1. I’m not sure if you’re suggesting that settler Australia as a whole hasn’t benefited from the dispossession of the Indigenous population. Whether or not this requires guilt is another question, but from your comments above it seems like you doubt it at all, which is surprising to say the least.

2. More important than the debate around settler benefit is the non-debate over Indigenous disadvantage. Sorry Day refers to the Stolen Generation specifically, but in practice it refers, as I think you assume in this post, to the general disadvantage and hardship inflicted upon the Indigenous population of Australia. These are not just particular events that occurred before we were born or even before our parents or grandparents were born, but refers to a system of colonisation which is still being felt in very real ways by the Indigenous community today. The most relevant point of Sorry Day is not to commemorate past atrocities but to point out that over two hundred years after the first fleet, Aboriginal people are still systematically disadvantaged.

3. Do you think the government should have apologised as they did? There is a distinction there between a government apologising and a nation apologising; I wonder what you make of it.

4. ‘Sorry’ does not always imply guilt. In its many different connotations for Sorry Day, I believe one of the strongest is mirrored in one of the Sorry Book quotes you display above: “I’m so sorry for your suffering.” Sorry Day is at its most potent when the feelings it encourages are empathy and sympathy, rather than guilt, pity or personal culpability. And I think that is one of the crucial reasons for Sorry Day’s existence, as so many Australians are still so absurdly misinformed not only about the history of colonisation of Australia but the current circumstances in which you find yourself if you are happened to be born with Indigenous heritage. This misinformation – fuelled as it was by John Howard’s stubborn attachment to the notion that ‘we’ in the present are not responsible for past actions – is surely one of the biggest causes in the persistence of such disadvantage.

May 31, 2010 at 10:55 pm |

I agree with Daniel’s comments. For me Sorry Day is about acknowledgement of the past. About admittting and accepting that the Stolen Generations and other past injudices were committed, and in acknowledging them taking a step forward in resolving resulting issues. I don’t see it as an issue of responsibility and guilt so much as admmittance of it occuring, and that it was not a positive thing.

June 1, 2010 at 5:16 am |

Thanks for the comments, guys. Zoe seems to agree with Dan’s point 4, so I’ll start from that and work backwards.

I’m in favour of expressions of empathy and commiseration. Maybe I’m confused, but I seem to remember that even Howard, without an inch of goodwill, eventually submitted to that – something like “sincere and deep regret”. But I’m less interested in what the creators of Sorry Day intended it officially to mean, than I am in what it turns out to mean for people generally. And it seems impossible to deny that “sorry that X occurred” often slides into “sorry for doing X.” This is no misrepresentation of mine. Keep in mind that the people running the Sorry Book website have chosen the above messages as somehow exemplary. The misunderstanding of these children (that Sorry Day involves “white people” apologising for “what we did to black/brown people”) is not fortuitous or accidental. Similarly, it’s not through ignorance or innocent error that children at Anzac Day commemorations always speak of the AIF having fought for democracy and freedom. Who “invites” them to do so?

I have no problem with state apologies, though given the NT Intervention, the verboten subject of reparations, and the rest, one must wonder at its sincerity or utility.

The remedying of present-day disadvantage (a weasel term, you’ll agree!) is, it seems to me, not very well served by Sorry Day, at least not a Sorry Day where participants use the terms of racial collective responsibility. And it will be difficult to stop ordinary people using these terms to understand the past while historians continue gleefully to do so. On the other hand, compassion seems worthwhile if politically not that useful. But I certainly wouldn’t want to argue against it. I’m well aware that the genocidal effects of colonialism don’t all lie in the past, but don’t think the structural position of Indigenous people in contemporary Australia is well captured by the idea that Aborigines constitute an internal colony. Australia isn’t an ongoing, active settler colonialism like Israel.

The question of “benefit” from colonisation is hopelessly difficult, and not at all useful in understanding, describing or overcoming the effects of colonisation. If it’s not taken as a mere metaphor, then any criteria you impose on the list of beneficiaries will rapidly be shown to be arbitrary. If a woman of Irish ancestry doing backyard piecework in 1880s Melbourne can be said to have benefited, then so may the Chinese, Indian and South-Sea Islander families receiving remittances from diasporic coolies, goldminers or plantation workers. If displaced people emigrating from postwar Europe can be said to have benefited, why not a contemporary Mexican drinking soft drink from a cheaply-purchased aluminium can manufactured from Australian-mined bauxite? No, if the history of neoclassical economics teaches us anything, it’s that utility as a theoretical concept should be marked “wrong way: go back!” Better to stick with rigorous questions: like who expropriated whom, who got the surplus product, who brought the smallpox (a controversial topic!), who took the children, who opened the missions and who fired the guns. And in all cases, “settlers” or “white people” is not a correct or useful answer.

June 1, 2010 at 6:32 am |

Hello all, I’ve found reading this most interesting, perhaps mostly because I’ve been doing research recently into the history of land use in the Geelong area, trying to go back as far as possible to the earliest European landowners. Of course, I haven’t written a thing in my reports about colonisation or Indigenous occupation, for this is not what the clients are after and I’m not an archaeologist. But I must admit it has rankled with me a little as I read about the these pastoral pioneers’ barley growing and sheep rearing, that I’m not getting the full picture about the real history of the land.

Anyway, I think I need to read this a few more times to get a proper grasp of your argument, Nick (you know how my simpler brain struggles to understand all your smartness and stuff). But a couple of things that have struck me:

1. Not only is compassion worthwhile, Nick, it is crucially important. You say that compassion is not politically that useful. I say that compassion for the situation of Indigenous people, combined with proper understanding of our past and how we have come to this, is the only way that political change will occur with any positive effect. Guilt is certainly in no way helpful, and doesn’t make sense, and it is frustrating to see children picking up such a message, but at least we’re getting somewhere don’t you think? At least those kids have learned something about the history of this country and the reason for Indigenous disadvantage – at least they have developed some understanding and compassion. Though it may be misguided and we obviously have far to go as a nation (understatement), I think it is encouraging to see such a development.

2. Your final paragraph referring to Ann Curthoys: I was wondering if you could explain further what you mean about both versions being false. If you argue that the more useful response is that neither is completely true and therefore they are both false, it then seems to me that you are arguing it is useless to search for any historical truth at all – unless you find the WHOLE truth. But perhaps I’ve misunderstood. I do tend to get rather unnaturally excited at debates over historical truth 🙂

June 1, 2010 at 7:13 am |

Hey, Fi. I say that compassion is unlikely to be politically useful because I can think of no historical example where compassion (by some people for another) has produced any kind of progressive political change. Change may occur, though, when people become aware of common interests, whereupon they have an incentive to fight together for a goal. It’s recognition of that common interest, rather than compassion per se, that I think should be fostered. (Note that I’m only speaking of a political arithmetic here: compassion does have other values. I think it’s a Good Thing that, since the 1970s, academic historiography has dealt with this stuff, and that kids get taught the horror of Australian colonisation).

As for the last paragraph from the post: it’s not that I think either version is a little-bit true. They’re both wholly false, as is any Volkgeschichte (history of the race). In general I’m a philosophical realist, and strongly opposed to postmodernism and epistemological relativism, so I believe some versions of history are more true than others. It is possible asymptotically to approach the WHOLE truth by eliminating error, but impossible to reach it.

June 1, 2010 at 1:10 pm |

This is where I wish wordpress would allow me to quote comments in my response. This could get unwieldy!

Maybe I’m confused, but I seem to remember that even Howard, without an inch of goodwill, eventually submitted to that – something like “sincere and deep regret”.

Yes, but that was in his position as Prime Minister, which was a wishy-washy position from my point-of-view, as the government is the only body that can effectively actually apologise for deeds done rather than to express sympathy (which of course as you point out, was not really sympathy at all).

And it seems impossible to deny that “sorry that X occurred” often slides into “sorry for doing X.”

Yes. But I still think you’re giving too much weight to the idea of Sorry Day as being one of collective white guilt. This is not what it is for me, and I do not believe I’m isolated in that view.

Better to stick with rigorous questions: like who expropriated whom, who got the surplus product, who brought the smallpox (a controversial topic!), who took the children, who opened the missions and who fired the guns. And in all cases, “settlers” or “white people” is not a correct or useful answer.

This is a pretty simplistic and narrow view of what actually occurred. The nature of racism and colonialism are such that overt actions of aggression and oppression are rarely the most common expressions. These are insidious forces that do not often find themselves being controlled by such easy and definable targets as state protectors and heads of the Rum Corps. It is not as simple to charge the proponents of colonialism as it is to put violators of war crimes on trial. These are modes of discourse, of thinking, of ideology that are widespread and far-reaching. You can find them both in religious organisations and religious individuals; both in mandatory detention laws and in individual policemen in the Northern Territory; both in systems of education and in educators; both in football commentators who claim Indigenous footballers are “magic” and the forces which dictate that the only career path open to many young Indigenous boys is to kick a football around.

Once we have tracked down all the individuals who fired the guns, so to speak, does the systemic exclusion, oppression and disenfranchisement of Indigenous people stop? In the case of colonial and racist attitudes, self-perpetuating systems which often infect the minds of those it seeks to oppress, the question of “who” very quickly becomes unhelpful.

I can think of no historical example where compassion (by some people for another) has produced any kind of progressive political change.

I’m not sure if this is the sense of political change that you’re using, but wouldn’t you say an organisation like Amnesty International uses compassion pretty much as its political bread and butter? How else do they assemble such huge letter-writing campaigns (which do achieve some sort of tangible change – like freeing political prisoners or changing laws)? Because the letter writers feel they have a common interest?

In general I’m a philosophical realist, and strongly opposed to postmodernism and epistemological relativism, so I believe some versions of history are more true than others.

I don’t necessarily think that postmodernism disallows the notion that some versions of history are more true than others. If you’ll excuse me, I’ll just go and get my can opener for this batch of worms that recently arrived…

June 1, 2010 at 1:52 pm |

I still think you’re giving too much weight to the idea of Sorry Day as being one of collective white guilt. This is not what it is for me, and I do not believe I’m isolated in that view.

Of course you’re not isolated, as I’ve already admitted. But you can’t simply ignore that other idea, or pretend it’s unrelated.

The nature of racism and colonialism are such that overt actions of aggression and oppression are rarely the most common expressions. These are insidious forces that do not often find themselves being controlled by such easy and definable targets as state protectors and heads of the Rum Corps. It is not as simple to charge the proponents of colonialism as it is to put violators of war crimes on trial.

As I’ve already suggested, the most damaging aspects of Australian settler colonialism was not overt violence – it was the expropriation of land, its distribution to graziers and their setting up of pastoral production that was most disruptive to Indigenous societies. Neither that, nor smallpox, which was responsible for most of the deaths, is very visible. These were long-term structural processes which involved changing the forms of subsistence available to Aboriginal people, behind their backs as it were. These processes did not have names or faces. Nonetheless we can reliably point to them as causes.

Once we have tracked down all the individuals who fired the guns, so to speak, does the systemic exclusion, oppression and disenfranchisement of Indigenous people stop? In the case of colonial and racist attitudes, self-perpetuating systems which often infect the minds of those it seeks to oppress, the question of “who” very quickly becomes unhelpful.

I am eager to ignore the “who” and understand the history as a “process without a subject”, as the saying goes. It is those who I criticise who’ve invented the imaginary agent, “white people”, who must bear moral culpability. Yes, I’ve pointed to the historical figures who seem to have causal responsibility, but only with the aim of identifying the social forces and broader processes they respresent.

I’m not sure if this is the sense of political change that you’re using, but wouldn’t you say an organisation like Amnesty International uses compassion pretty much as its political bread and butter?

You probably wouldn’t like to hear my view about that sort of thing :p

I don’t necessarily think that postmodernism disallows the notion that some versions of history are more true than others.

Of course, there are many breeds and creeds of postmodernist. I was referring broadly to Foucault’s argument that truth (at any given moment) is the outcome of a balance of social forces, for which view it is impossible to talk about a gradation of truth.

June 2, 2010 at 2:20 am |

Also, in response to this:

This is a pretty simplistic and narrow view of what actually occurred. The nature of racism and colonialism are such that overt actions of aggression and oppression are rarely the most common expressions. These are insidious forces that do not often find themselves being controlled by such easy and definable targets as state protectors and heads of the Rum Corps. It is not as simple to charge the proponents of colonialism as it is to put violators of war crimes on trial. These are modes of discourse, of thinking, of ideology that are widespread and far-reaching. You can find them both in religious organisations and religious individuals; both in mandatory detention laws and in individual policemen in the Northern Territory; both in systems of education and in educators; both in football commentators who claim Indigenous footballers are “magic” and the forces which dictate that the only career path open to many young Indigenous boys is to kick a football around.

Our point of contention wasn’t whether the effects of colonialism/racism were diffuse and included modes of speech, everyday behaviour and attitudes. That fact is plainly true. The question was whether we could talk effectively of “who benefits?” I believe I demonstrated in my next-to-last post that we couldn’t.

Perhaps you’re suggesting that anyone who, say, uses racist turns of phrase or practises so-called “microagression”, is benefiting somehow? This can only be a metaphorical usage.

At any rate, I will point to what I think is the Foucauldian provenance of this thinking. It seems to go something like this (forgive me if I’m misrepresenting):

(1) The effects of racism/dispossession/marginalisation are dispersed throughout the society, penetrating even stuff like football commentary.

(2) Because it shapes people’s vocabulary and everybody behaviour, racism/dispossession/marginalisation forms part of their very self-identity.

(3)Because racism/dispossession/marginalisation is therefore “performed” and reiterated by almost everyone as part of their social existence, it cannot be localised in any particular social forces.

In contrast, I think the situation of Indigenous Australians is a glaring illustration of the inadequacy of this thinking. Power radiates out from certain points (the state and propertyholders) and is applied at certain concentrated points, where the people are oppressed.

June 3, 2010 at 2:35 pm |

Just marking that I’m definitely coming back to this, I’m just snowed in marking at the moment, and have had quite enough of dissecting arguments as a result!

June 13, 2010 at 2:45 pm |

[…] based on national ancestry, popular with some on the soi-disant left. My examples came from the Sorry Book, Christian anti-semitism and Bernhard Schlink. But somehow I forgot one of the great symbolic […]

January 9, 2011 at 11:08 pm |

[…] conflict in colonial Tasmania, for example, is frequently portrayed as a matter of rival groups (“black” and “white” people, or European and Indigenous people), each with an incompatible claim to exclusive possession of […]

November 1, 2011 at 8:52 am |

[…] solidarity within the working population and to encourage allegiances across class lines. It prompts people to align with their ‘race’ or nation as the primary object of collective identification, and confuses them about who benefits from […]

May 14, 2012 at 2:30 pm |

[…] On the other hand, among ‘progressive’ left-liberal commentators, scholars and activists there is little concern or thought for questions about property relations. There is, however, much nostalgic Schwärmerei for the Whitlam and Keating ALP governments, and accordingly little critical understanding of policies implemented under those administrations. The unquestioningly favourable opinion of progressives towards Indigenous land rights and native title is encouraged by the emergence, since the 1990s, of declarations of opposition made by conservative political parties and figureheads, who have led advocacy of a transition towards fuller private property. The interpretative infirmity of left-liberals is compounded when, under the sway of nationalism and identity politics, such circles implicitly deny the existence of social or class divisions between members of the same ‘race&#…. […]

June 14, 2012 at 5:26 pm |

[…] historian. William Deane, the former High Court justice and Governor General appointed by Keating, declared that the criminal horrors of Australian colonialism were ‘properly to be seen as acts of the […]

June 22, 2012 at 2:19 pm |

[…] and other forms of economic governance, child-rearing practices, schooling and constitutions. Australia and Hawaii can stand as examples of these practices, and of the devastation they […]

June 25, 2012 at 2:36 pm |

[…] an idiosyncratic treatment. The nation as collective actor was similarly invoked at this time by Sir William Deane and by Paul […]

July 23, 2012 at 8:37 am |

[…] on nationality – the Michael Hanekes and Bernard Schlinks of his day, the Daniel Goldhagens, William Deanes and Paul […]

October 7, 2012 at 12:48 am |

[…] unique and shared interests of (say) women, young people, Dalits, ‘yellow people’, Indigenous people, etc. These fundamental interests are held to conflict, in one way or another, with the interests […]

February 13, 2013 at 9:51 am |

[…] I’ve devoted several posts here to criticizing the notion of collective responsibility for so-called ‘national’ wrongdoing, of popular liability for ‘acts of the nation itself’ (William Deane). […]

March 31, 2013 at 10:11 pm |

[…] an idiosyncratic treatment. The nation as collective actor was similarly invoked at this time by Sir William Deane and by Paul […]

February 14, 2015 at 9:22 am |

[…] is compounded when, under the sway of nationalism and identity politics, such circles implicitly deny the existence of social or class divisions between members of the same ‘race&#… (or, from the opposite direction, reject the idea that a commonality of interest unites members of […]

February 24, 2015 at 12:15 am |

[…] I’ve devoted several posts here to criticizing the notion of collective responsibility for so-called ‘national’ wrongdoing, of popular liability for ‘acts of the nation itself’ (William Deane). […]