Accepting the 2001 Sydney Peace Prize, Sir William Deane, former High Court Justice and Australian Governor General, delivered a lecture on ‘The Search for Aboriginal Reconciliation.’

In it he remarked:

[The] oppression and injustice to which indigenous Australians were subjected in our land and under our Federation were not merely the acts of individuals who are long since dead and for whose acts living Australians might deny responsibility. They are properly to be seen as acts of the nation itself of which all living Australians are members. As such, that past oppression and injustice remains part of the very fabric of our country. They reach from the past to blight the present and to demand redress and reconciliation in the future.

Subscription to these views is commonplace and widely considered to be ‘progressive’.

Since the early 1990s, one wing of the Australian ruling elite, having embraced such pieties as useful to its interests, has encouraged their diffusion throughout public opinion under the banner of ‘reconciliation’.

Journalists and academics, apt to take their cue from official sources, have typically followed.

Socially respectable, this conventional wisdom is now promoted by left-liberal organizations like the Sydney Peace Foundation as a necessary part of acknowledging and helping to repair the awesome genocidal catastrophe of Australia’s European colonization.

For much of Australia’s broader non-Indigenous population, stirred by genuine sympathy for the injustices and depredations inflicted on Indigenous people, illusions persist about the purpose of what is presented to them as a kind of national atonement.

The country’s political establishment, for reasons of expedience, promotes collective expiation as a way to ‘heal wounds’ and allow ‘new partnerships’. Editors and executives have approved the project as a matter of ideological etiquette and table manners.

But Deane’s lofty notion of collective guilt — underpinned by a vision of ‘the nation’ as a collective moral agent, a persona ficta capable of undertaking actions and bearing culpability for them — has an unpleasant heritage, questionable logic and reactionary political implications.

Let me explain what I mean, since to say all this is to reverse the evaluative claims typically made for these ideas by the state, the media and intelligentsia. Questioning the political packaging in which such ideas are draped, and the aisle and shelf in which they have been placed in the ideological supermarket, is bound to be jarring.

Many politically conservative people also reject statements like Deane’s above, and for bad reasons. Wary readers may fear that I will present similar arguments here. They may even believe that someone rejecting views like Deane’s is thereby somehow obliged to endorse some right-wing belief or sentiments. Or they may think that any criticism lends succour to the political Right or is strategically unwise for those with politically opposite views (e.g. because it lessens the confidence of the enemies of the political Right).

But I think that the opposite is true. I believe that views like Deane’s — the idea of ‘national responsibility’ for one of history’s great crimes, ‘the oppression and injustice to which indigenous Australians were subjected’ — are inconsistent with the cause of understanding and addressing the evils of settler colonialism. Affirming them, far from encouraging ‘redress’ of the consequences of that crime, hinders it.

We therefore can (and indeed should) reject such views for reasons independent of the reasons that political conservatives deny them. And we can relax from fears that we are being counterproductive or unwittingly advancing the aims of the political Right.

What does it mean to speak, as Deane does, of inherited responsibility for ‘acts of the nation itself of which all living Australians are members’?

Firstly, his claim that guilt is laterally transferred — i.e. that a supra-individual entity or group (an entire nation, race, gender, etc.) is responsible for the behaviour of the member individuals who make it up — is accompanied, as usual, with the pendant idea that this group liability is transmitted vertically across generations, a mortmain of culpability (‘Let his blood be upon us, and on our children’).

The latter has been a traditionally toxic formulation wherever it has been introduced.

Yet maybe there is nothing wrong with the notion, so long as it is applied properly — say, to a genuinely powerful group, rather than an oppressed minority. Its dubious precursors aside, is there any sense to the idea? Does it capture something about settler colonialism that other critical accounts of Australian history neglect?

Let’s run through the ideological vision as it’s propounded by official sources such as Deane.

In Australia, as with the biblical case of ‘collective guilt’, causal responsibility for the wrongful deeds is acknowledged to lie with specific historical agents, natural persons who may be named and arraigned: individuals and entities including colonial administrators, military officers and police, pastoralists, ‘gentleman settlers’, magistrates, civil servants, Chief Protectors, missionaries and miners, having acted both singly and in concert.

But surely all these people and organizations were not working independently of each other, in separate enterprises that did not in some sense cohere into a larger shared project of colonization. So, in the Australian case as elsewhere, an additional degree of moral blame (culpability) is attributed to a macro-agent: conceived of as a particular identity group, whose members share the same (putative) racial, ethnic or national identity as the direct perpetrators.

For the group is believed to constitute a kind of supra-individual personality (a reified ‘white people’, ‘the Jews’ or ‘the nation’), capable of having beliefs, pursuing goals and undertaking actions.

The collective identity of this group is held to persist across time, despite changes in personnel. It has a ‘general will’, which is something more than (i.e. can’t be reduced or decomposed to) a mere aggregation of individual wills. Like a limited liability company (rather than a partnership), it survives the departure of those specific individuals who bear the stain of direct causal responsibility.

Indeed, it’s possible to see the action for which blame was incurred as having somehow been undertaken by the collective entity.

The apportionment of culpability to the responsible individuals thus doesn’t exhaust things: a residue of guilt must be attributed to the supra-individual entity itself (‘vicarious liability’), and thus to all individuals who constitute it.

Guilt thereafter accrues to later-arriving members of the collective personality, i.e., individuals who possess the attributes by which group membership is defined. A kind of metaphysical guilt thus ‘reaches from the past’ down to members of subsequent generations. So long as the putative ‘nation’ or ‘race’ endures, and until the liability is discharged, the guilt of its members is undying.

Guilt for ‘what he or she has done to others’ thus taints each person descended from the perpetrators of ‘white aggression and racism’. On Sorry Day, and in Sorry Books, non-Indigenous people are invited to imagine themseves as ‘white’, then to express contrition for the past behaviour of fellow ‘white people’.

Of course, the völkisch basis of inherited responsibility may be downplayed.

In such cases, it won’t be claimed that a nation or race is the type of foresightful, purposeful collective actor that can do something, such as commit a moral wrong. But it’s held that such an act can be performed on its behalf (i.e. to its collective advantage), so that its members thereby incur a debt or degree of culpability.

Thus, for the ANU historian Ann Curthoys, all non-Indigenous Australians today bear guilt as ‘the beneficiaries of the colonisation process’.

But cui bono? is, to say the least, an unorthodox way to determine moral responsibility (the awful Susan Brownmiller is a rare proponent of the idea). Culpability for some harm inflicted on another isn’t usually thought to follow from the mere fact of having benefited, ex post, from that injurious act or occurrence.

That aside, Curthoys leaves unargued exactly how the entire non-Indigenous population — rather than some small subset of it — has benefited from the devastation of Indigenous Australian societies.

Do Deane and Curthoys not bestow a curious anonymity on the political agents responsible for these sinister deeds, and disguise the purpose of their enterprise? Is the villain of the piece, ‘the nation’, or ‘white people’, not a pure abstraction?

More importantly and troublingly, the upshot of Curthoys’s claim that ‘all migrants and their descendants’ have ‘benefited from colonisation’ is that Australian history (and current political circumstances) must be understood simultaneously as a zero-sum conflict between Indigenous and non-Indigenous groups and a harmonious ‘common-interest game’ within each respective group.

That is to say, on Curthoys’s vision the two ethnic groups have contended over relative shares of some pie. More for one group has meant more for all members of that group and less for all members of the other group.

Thus conflicts of interest within groups are entirely absent, while pure conflict exists between groups: the fortunes of members of one group (Indigenous Australians) vary inversely with the welfare of all other people.

The political implication of this argument is dire and reactionary: if A benefits by inflicting some loss on B, then B can only gain or recover the loss at A’s expense, in which case A isn’t a credible ally for any project by B to advance its material interests, for in doing so A would be harming itself.

B can only satisfy its wants by breaking with A; or as Thomas Schelling explained:

[In a] common-interest game we can refer to [the players] as ‘partners’ and in the pure-conflict game as ‘opponents’ or ‘adversaries.’

The spread of such beliefs upholds the political exclusivity of groups defined along ethnic (or linguistic, religious etc.) lines. It partitions members of populations who otherwise might act in political concert, while suppressing other salient social distinctions (e.g. class) that might otherwise lead to political divisions.

The prospect of working-class unity is thereby neutralized, and this surely is one reason why Australia’s political elite has found promotion of these ideas to be expedient.

Of course, this doesn’t speak to the truth of Curthoys’s factual claim. Whether or not it’s to be preferred shouldn’t be decided on the grounds of political handicap or usefulness, but on whether or not it provides a true description of historical events.

Like the children’s messages scrawled in the Sorry Book above, the portrayal of Deane and Curthoys obscures the actual causal process of settler colonialism.

The Australian genocide, in its initial high-impact decades, involved the British state assuming radical title over fertile land, then distributing it and other assets to graziers and farmers. This seizure and re-allocation of resources was enforced through direct violence (by the state and by private agents of the new owners).

More crucially, the creation of possession-based property rights over economic resources entailed the denial (in the name of the owner’s exclusive dominion) of access and use by non-owners to their hitherto secure means of livelihood: hunting grounds, watering holes and shelter. That ousting dealt a massive shock to previously stable practices of subsistence acquisition and societal reproduction.

Worldly things and domains that formerly were open-access were suddenly no longer available for non-owners to satisfy basic needs, undertake sustenance-drawing activities or secure personal livelihoods.

Disruption to the existing regime of self-provisioning, sharing and related types of food production produced a sudden reliance for material subsistence on wage income, market exchange, charity or other novel transactions. This in turn disrupted the kinship practices and forms of cultural transmission that governed pre-colonial Australian societies.

Colonial authorities (and their successors) then attempted, in the manner of war victors, to eradicate the cultures, behavioural patterns and child-rearing practices of the defeated forager societies, and to replace them with norms and preferences more suited to the new market-based economy.

High fatality rates followed exposure to new disease environments. The latter arose through (i) the creation of high-density settlements in what formerly were sparsely populated areas, (ii) population displacement through inter-regional labour markets, and (iii) the introduction of alien pathogens by the colonizers.

Together with disruption of kinship systems and breaking apart of social units, this led to imbalanced sex ratios: changed sexual practices then encouraged the spread of venereal diseases, which led to a sharp and prolonged fall in fertility.

Such catastrophic social disruption then produced the sort of dysfunctional behaviour displayed regularly, over the past five centuries, by peoples defeated by capitalist imperialism: alcoholism, prostitution and high rates of interpersonal violence.

Of course, the displacement of one society by another carrying a novel set of institutions (involving, among other things, catastrophic demographic decline in the original population, and mass export of a new settler population) is something very different from a simple on-off event (say, a crime committed by an individual person). A process on this scale, to the extent that it involved deliberate design, required the coordination of many diverse participants into institutional collectivities (corporate bodies like civil service departments, military units, business firms, clubs and political organizations).

In these collective entities, group solidarity and a sense of common purpose were regularly maintained by appeals to a shared European ancestry. Ethnic stratification, rather than class membership, often was the ideological basis for distinguishing insiders from outsiders.

But it’s quite a step from acknowledging this to suggesting (as today’s socially sanctioned authority figures and cultural models obviously have done to the children writing above) that colonization (and post-Federation rule) was somehow an expression of the ‘general will’ of ‘white people’ or ‘the nation’.

The ways in which historical actors (sometimes) described, legitimized or understood their own activities ought not to govern our understanding of those activities today.

Historian Marilyn Lake has said:

Aboriginal people were active in identifying all settlers – whether hut-keepers, clergymen, convicts or military officers – as one people, as ‘white men’, whom they held jointly responsible for taking their land… [The indiscriminate nature of] Aboriginal retaliation and revenge… is explained by the Aboriginal perception that a group of people defined by their ‘whiteness’ had taken their country.

Supposing this was in fact ‘the Aboriginal perception’, it was a mistaken and regrettable (though entirely understandable) one. The tangible resources of Australia were seized by, and property rights in them apportioned to, a very small group of people, all of whom had European ancestry.

But none of these property holders could sensibly be defined by their ancestry, since the vast majority of ‘white men’ did not (as today most non-Indigenous Australians do not) own productive assets.

In this respect, the concentrated pattern of landholding that emerged during the mid-19th century in the Australian colonies may be distinguished from that which resulted from the Ottoman genocide of Armenians during the First World War.

In the latter case, title deeds to plundered Armenian estates, farms, workshops, factories, orchards and vineyards were allocated broadly to the Anatolian peasantry.

In the eastern Australian colonies, no such egalitarian smallholding grew up on the land confiscated from its displaced and hunted Indigenous inhabitants.

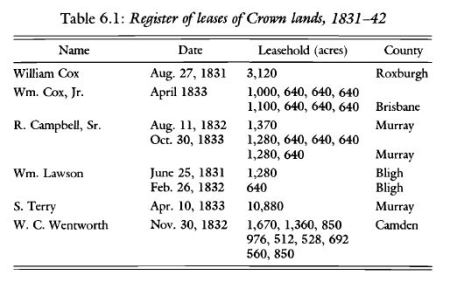

In the initial decades following British settlement, land grants were dispensed to military officers and other favoured clients of the governor. Later, from the 1830s, this narrow patronage system was replaced by land sales along Wakefieldian lines, designed to guarantee a supply of labour to capitalist employers.

The ‘sole object’ of a land price, declared Wakefield, was ‘to prevent labourers from turning into landowners.’

Cultivable or grazing land was henceforth accessible only to the wealthy and creditworthy. In 1851, 31 million acres of the Port Phillip District were held by fewer than 1000 squatting licence-holders.

Ownership was further consolidated as the nineteenth century progressed.

The picture of ‘white’ yeomanry dotting the Australian continent, although a powerful ideological symbol, was nothing more than an image d’Épinal. From the outset colonial New South Wales was an urban society, not a peasant one.

Secondly, with regard to Lake’s claim, the ‘collective actors’ responsible for colonization were exclusive institutions which left almost no room for popular participation.

During the first 70 years of their existence, the Australian colonies concentrated decision-making authority in a tiny number of people. For four decades after settlement New South Wales was a military dictatorship (what Bayly called the ‘proconsular despotism’ common throughout the Empire between Pitt and the Reform Bill). For the next 30 years, autocratic rule was broadened to include an oligarchic elite, allowing the voice of special interests, especially graziers and merchants, to be heard.

Thereafter, the formation of representative assemblies and broadening of the franchise made elite decisionmaking only weakly accountable to the vast majority of the settler population: members of the subordinate and asset-free classes. And by this time (indeed, even by the 1830s), many of the most consequential decisions concerning the fundamentals of Australian life (where economic activity would occur, and how, etc.) were made by powerful private actors (pastoralists and banks) whose property rights kept their decisions beyond the reach of democratic accountability.

Thirdly, while the devastation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander societies did require the decentralized action of many people from various economic classes (i.e. something broader than a narrow elite coalition), this didn’t involve the deliberate pursuit, in unison by all settlers of European ancestry, of shared goals.

It did, however, involve the (unplanned) coordination of these individuals, via a set of rules, institutions, constraints and incentives which governed how the members of colonial Australian society interacted and behaved, such that social development was channelled in a particular terrible direction.

This set of durable rules governing Australian society was not decided by the broad population in any electoral vote or constitutional convention. Nor were many of the institutions spontaneously accreted over decades. They were laid out purposely in royal charters and letters patent, and in strategic documents like the Bigge reports.

How did this work?

There were, as there are in each society, a set of economic institutions and social relationships governing how individuals could acquire a livelihood (i.e. what they had to do or be to acquire the goods and services needed to survive).

Thus Australian forager societies, before the arrival of British colonizers, involved customary rules of sharing and division, norms which Indigenous populations struggled to maintain subsequently, as described above. These rules then constrained who interacted with whom, the terms on which they met, the rights and obligations of each party to the transaction, etc.

And, in colonial Australia as in any society, the most important of these rules (those defining the set of feasible actions available to individuals and the payoffs attached to them) were the definition of property rights in economic resources, and their allocation to particular individuals, and the contracts (i.e. the type of social relationships) available to people given their level of wealth.

By virtue of (above all) what resources they did or didn’t possess, members of the various classes that made up post-1788 Australian society were compelled to act in particular ways, prevented from behaving in certain other ways, or otherwise had incentives which predisposed them to do some things and not others. This was what Jon Elster called ‘endowment-generated behaviour.’

But today’s ‘progressive’ opinion cannot confront these matters, for to seriously investigate the historical record would lead to undesirable political conclusions. Thus Sorry Day and its backers discourage anyone from inquiring into the social relationships underlying the devastation inflicted on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island people.

Yet lapidary and insightful description of this genocidal process does exist.

It can be found, for example, in the work of Rosa Luxemburg, who wrote in 1913 of how ‘modern colonial policy’ seized ‘the land, its hidden mineral treasure, and its meadows, woods and water, and further the flocks of the primitive shepherd tribes’ that occupied ‘vast tracts of the globe’s surface’ outside Europe:

Since the primitive associations of the natives are the strongest protection for their social organizations and for their material bases of existence, capital must begin by planning for the systematic destruction and annihilation of all the non-capitalist social units which obstruct its development…

From the point of view of the primitive societies involved, it is a matter of life or death; for them there can be no other attitude than opposition and fight to the finish – complete exhaustion and extinction. Hence permanent occupation of the colonies by the military, native risings and punitive expeditions are the order of the day for any colonial regime. The method of violence, then, is the immediate consequence of the clash between capitalism and the organizations of a natural economy which would restrict accumulation.

This, written 100 years ago in Europe, is a vastly more accurate, devastating and useful account of the criminal policy behind the Australian genocide than the pious self-mortification about ‘acts of the nation’ promoted today by the Sydney Peace Foundation and other progressives.

By scattering historical focus away from the collective action of propertyholders and state elites (and away from the institutional evolution they begat), and towards a putative ‘white people’, the account of Deane, Lake and Curthoys harmlessly distributes the guilt of perpetrators across time, till both all and none are to blame. And, as Deane says, without understanding liability, it’s impossible to propose an appropriate remedy.

Curthoys does, however, make a useful contribution. This is to suggest that the ‘black armband’ and ‘white blindfold’ historians are two sides of the same coin.

For both groups, the central problem of Australian historiography is the moral status of ‘white’ people:

Looked at more closely, the contest over the past is perhaps not between positive and negative versions, but between those which place white Australians as victims, struggling heroically against adversity, and those which place them as aggressors and perpetrators, bringing adversity upon others.

Curthoys’s predictable stance is that both positions are, in a sense, true: at least both are ‘narratives, stories about the past which make sense to those who tell and receive them.’ A more useful response, surely, is that both versions are false.

It is not as moral melodrama, in which ‘white’ and non-white Australians contest, that the awful episodes of colonial history are best organized and understood. Instead something like Luxemburg’s version does much better, both as description and analysis of the facts, and as basis for political action.