In the 1960s, ‘Papua New Guinea came out of the bottom drawer of Australian politics’, according to the memoirs of the colony’s final administrator, Les Johnson.

Relinquishing the South Pacific territory — while preserving a legacy of favourable arrangements following departure — would demand more ingenuity from Australian officials than had direct rule.

The latter’s basic machinery and institutions had, after all, been inherited readymade from Canberra’s British and German predecessors.

London donated Papua, as a federation gift, to the new White Dominion in 1902; New Guinea was seized as war booty in September 1914, with an Australian Mandate granted later at Versailles.

Thereafter, besides fusing the administration of Papua and New Guinea in preparation for the Pacific War, few renovations were made while Port Moresby lay beneath Australia’s ‘warm, protective mantle’.

The colonial clinch was prolonged obstinately until the 1960s.

Yet, after Indonesian and Malaysian communism had been safely decimated — in 1966 Paul Hasluck sped to Jakarta to congratulate the new leadership — Canberra’s divestment of its largest Pacific possession followed swiftly.

The Dutch experience in western New Guinea doubtless taught its lesson. The Hague’s ponderous moves towards West Papuan independence, prolonged beyond toleration, had eventually been dealt a humiliating comeuppance. By 1962 the Kennedy Administration in Washington, wary of Asian anti-colonialism giving way to communism and Soviet aid, granted its blessing to Jakarta’s brisk annexation of the territory.

No such mistake would be repeated by the Australian government in the island’s eastern half. Yet Papua New Guinea was comparatively free of internal and external pressures, and Canberra could proceed towards self-rule with whatever haste or leisure it judged fit.

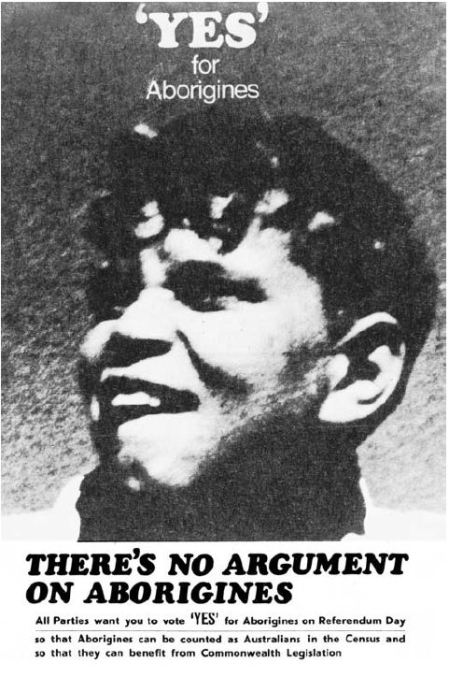

At the same time as this final colonial lap was taken, revision of protocols for rule over Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians also became a matter of (hitherto unknown) official urgency.

Each matter, when publicly ventilated, was draped in the lofty garb of self-determination and respect for customary practices.

Yet how to proceed, when Australian rule had in neither case prepared an educated elite, a cadre of lawyers and bureaucrats imbued with a sense of decorum and respect for property rights, to whom administrative powers could safely be passed, as elsewhere?

By the late 1960s a common solution, capable of general application, was settled upon.

Such coincidence of timing, and resemblance of outcome, were not due to happenstance.

Colonial administration of Canberra’s Pacific possessions, entrusted to the Department for Territories, thereby shared personnel (bureaucratic and ministerial), policy formation, institutions, recruitment and training with rule over the home territories.

This shared apparatus naturally contributed to a commonality of outlook and ideas. Officials and government anthropologists, trained in Sydney and Canberra for field service, shuttled between the Native Affairs branch of the Northern Territory Administration, and its counterpart across the Torres Strait.

Elite policy prescriptions for Darwin, Alice Springs and the Kimberley were prone to resemble those for Port Moresby, Bougainville and Nauru. (Civil administration in both Papua New Guinea and the Northern Territory had been suspended and replaced with direct military rule in 1942.)

Under the terms of a 1944 Canberra-Auckland agreement, postwar regional coordination — involving gradual decolonization of the vast archipelagic band that during wartime had fallen within the South West Pacific Command — was ushered via the tutelage of the South Pacific Commission.

Made up of European colonial powers and their US overlord, within this body Canberra played the dominant role.

W.E.H. Stanner, later a senior figure in the Council for Aboriginal Affairs, expressed hope that the South Pacific Commission ‘should bring the machinery of administration to the Pacific right up into the vanguard of progressive colonial policy.’

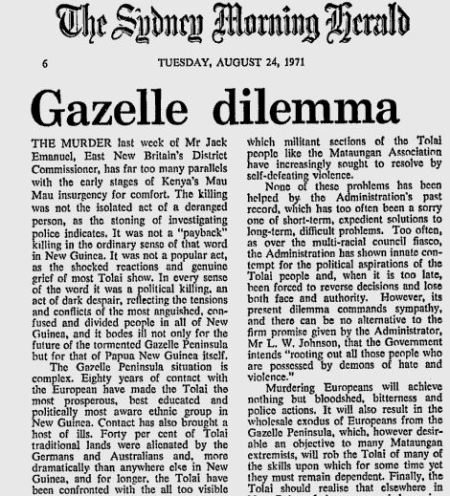

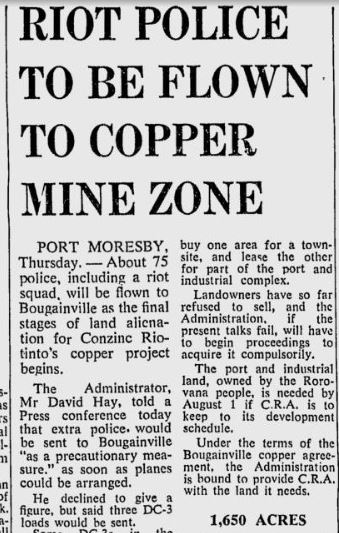

Property rights governing land in Papua New Guinea were thus codified during the 1960s and 1970s, in the waning years of Australian colonial administration.

The spread of mining and commercial coffee, cocoa and copra plantations had raised the price of land, especially in the highlands.

This made the demarcation of boundaries, and the apportionment to various parties of exclusive ownership rights, a high-stakes practice.

The existing informal system of adjudication, developed before the the novel institutions of capitalism had arrived, was deemed inadequate to the task. A formal system of land registration and administration was accordingly developed.

In preparation for Independence, the primary aim was to secure (against the risk of expropriation) freehold title and leases held by mining firms, commercial plantations, wealthy individuals and missions.

Of secondary concern was the vast stock of rural land, unalienated and not claimed by the Crown, occupied by low-yield subsistence tillers, who made up the overwhelming majority (>85%) of the population.

Colonial officials at first drew on the experience and advice of British land reformers in Kenya.

During the 1950s, in the decade before their departure, British authorities there had begun a countrywide effort to register private land titles, assign fee-simple property rights over consolidated plots, and promote cash-crop and plantation agriculture.

Just as in Kenya, however, the local PNG elite — about to assume political control and eager to consolidate the postcolonial social order — was not willing or able, as its inaugural act, to take up the enormous task of detaching smallholders from their farmland.

Rapid creation of a ‘class of landless people’, noted PNG’s Constitution Planning Committee, was likely to promote unwanted difficulties.

Among other things, low-productivity village farming set a very low floor (reservation price) for the wages of mining employees. Large-scale displacement of rural cultivators would have raised the cost to firms of hiring labour.

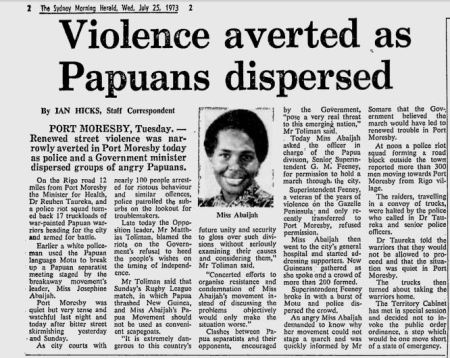

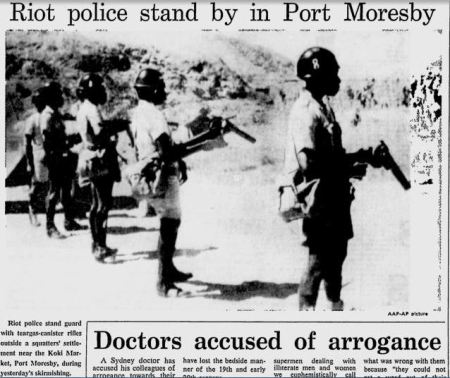

And it would have propelled much of the population into urban areas which, offering their residents few jobs or amenities, were already sites of social unrest.

The Land (Tenure Conversion) Act of 1964, aiming to grant freehold title to individuals, was therefore something of a dead letter. Johnson complained of ‘refusal to face up to decisions about land holding’:

We gave up and withdrew the Bills hoping that they might be re-introduced later, but mentally listing them as a problem for an independent government.

By the late 1960s, however, Australian policymakers developed alternative plans for vesting ownership of land and businesses in clan-based groups.

The latter were to be granted corporate legal status in order to secure title to property and ease conveyancing (sale, purchase, lease) between parties.

Disputes over land boundaries or title would be resolved through informal mediation by local courts.

In 1969 the Australian Joe Lynch, colonial parliamentary draftsman and chief author of the PNG constitution, gave voice to this position. Declaring ‘the undesirability of unnecessarily interfering with custom by forcing it into an artificial legal framework’, his terms were familiar from the annals of indirect rule:

The theme of the whole paper is simply that for too long we have all acted on the theory that indigenous forms of organization are not apt for “Westernized” economic development and that the latter must wait on a long period of “Westernizing” economic education. In my view, it is high time that we asked “Why not?” and tried to find remedies for specific deficiencies in the indigenous system. It is hoped that this paper may furnish a starting-point at least in the field of statutory requirements.

Under such a system, he noted, mining and forestry operations could proceed ‘in safety.’

The 1973 Commission on Inquiry into Land Matters provided legal mechanisms, and popular legitimacy, for this course.

Established under Chief Minister Michael Somare, the Commission was made up of Papua New Guinean members assisted by Australian advisers (along with the influential New Zealand-born, Melbourne-based historian Alan Ward). Its stated purpose was to promote ‘an evolution from a customary base; not a sweeping agrarian revolution; collective and individualistic extremes should be avoided.’

There policymakers, Australian and Papua New Guinean, followed the example of Fiji’s Native Land Ordinance, which had been enacted during the late nineteenth century under the colonial administration of the liberal Governor Arthur Gordon.

Under that arrangement (still in place today), property rights in land were assigned to mataqalis, or local clan groups of ethnic Fijians.

Contrived by Gordon with the help of a Fijian Council of Chiefs, this version of ‘indirect rule’ upheld political stability of the colonial and postcolonial social order. It increased the authority of the mataqali chiefs who (in the colonial period) collected taxes in kind and supervised the labour process of agrarian producers; now (in the present day) these figures oversee the disbursement of rents obtained from leases through the Native Land Trust Board.

During the 1960s and 1970s a related system was adopted in PNG.

As early as the late nineteenth century, the colonial administration of William MacGregor, a protégé of Gordon’s in Fiji, had attempted to ‘set up a system of indirect rule in British New Guinea’:

Endeavours have been made to strengthen the position of a number of leading men in certain tribes, so as to increase their authority and to put on them some responsibility towards the Government. A certain amount of progress has been made, but great patience is required, and it will be long before the position of any chief is sufficiently strong and authoritative to make him an efficient government officer.

Under MacGregor’s imperial successors, the luluai system allowed local notables to appropriate 10 percent of the rent extracted from villagers. Canberra had declined, however, to nurture an educated local elite to fill the colonial bureaucracy. ‘I am quite opposed to the development of a Papuan intelligentsia,’ declared the proconsul Hubert Murray in 1937.

In 1974, newly independent Fiji again provided the template for Port Moresby.

Following the Commission’s recommendation, groups — in which membership was defined by lineal descent, language or residence in a bounded territorial domain — were granted recognition as legal entities (Incorporated Land Groups).

Title to ‘customary’ land was vested in these bodies. The resulting corporate entity held exclusive rights of access and use, exercised decision-making authority, and received royalties and other payments. It could enter into contracts, sue and be sued, etc.

Through membership of an Incorporated Land Group (ILG), a large part of the PNG population retained direct non-market access to its means of livelihood (household farming plots and other tangible resources).

But, because an individual exercised this right (i.e. retained possession) by virtue of kinship or clan identity, parochial forms of allegiance were encouraged. According to Dan Jorgensen, recognition of landowning clans ‘tacitly endorse[d] the creation of politicised identities and attendant drawing of factional lines.’

This in turn led to a renewed deference and loyalty towards sources of traditional authority which had so recently seemed threatened by an intruding market economy. Inter-tribal warfare in the highlands provinces, now conducted using assault rifles and involving the razing of schools, increased dramatically during the 1970s, prompting the creation of a government commission during the mid-1970s.

To manage disputes over land ownership, a decentralized village-based judicial apparatus was erected, increasing the despotic power of ambitious big men and hereditary ‘chiefs‘. To such prominent and high-status figures was delegated the exercise of control rights (i.e. decision-making authority) over the land.

Farmers, entitled to access and usufruct, provided for their own subsistence and earned meagre cash incomes from marketing the remaining produce. Meanwhile ILG office bearers (who negotiated leases and other transactions with outside parties, such as mining and energy firms, fund managers and lawyers, and received and disbursed royalties and dividend payments) could receive annual incomes of 30 000 kina (A$15 000), many times the average national income.

Such offices have consequently become the object of tawdry power struggles and accusations of misappropriated funds. The signed consent granted by ‘community landowners’ to the Porgera gold mine was provided by just three men.

Case studies published by AusAID in 2007 found that ‘while more than 10,000 ILGs had been incorporated, the great majority were purely vehicles for entering into resource-extraction arrangements — in particular, for forestry, mining and petroleum’:

[The Land Rights Incorporation] Act became a convenient way for resource companies to fulfil their legal obligations to negotiate access to customary lands, and pay royalties to the landowners. The Act was rarely used as a property management system, and ILGs were reduced to “a conduit for receipt of cash”… As a result, many ILGs were reduced to passive rent collectors.

According to ANU economist Ron Duncan, these bodies, ‘set up to manage the revenues flowing to customary landowners from logging and mining activities, seem to have benefited only the people in charge.’

Around the time the Australian policymaking elite helped to build this institutional framework, it created something very similar at home.

Following the bipartisan decision to grant indigenous ‘land rights’ in Australia, bodies corporate, called land trusts or councils, were created to serve as trustees or agents for customary landowners. The communal title held by the latter was granted on the basis of group membership, defined through kinship, language, and residence or ties to a specific territory.

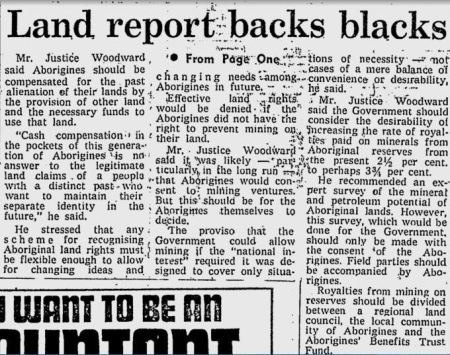

PNG’s Commission of Inquiry into Land Matters had sat around the same time (1973) as Australia’s Woodward Royal Commission into Aboriginal land questions (1974), and the former’s statutory outcome — the Land Groups Incorporation Act (1974) — shortly preceded the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act of 1976.

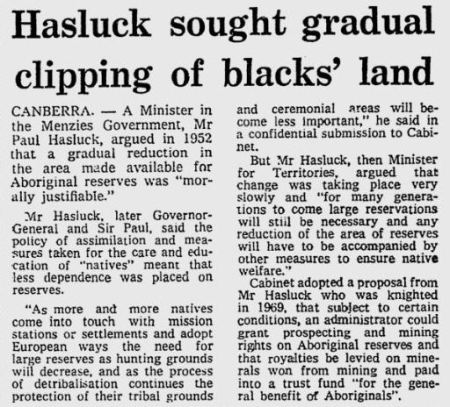

Throughout most of the postwar period, elite policy formation on the two issues had been tightly connected, as under the Menzies, Holt and Gorton governments the commonwealth departments of External Affairs and Territories were overseen by the same minister (Paul Hasluck followed by C.E.B. Barnes).

Policy intellectuals, civil servants and politicians such as H.C. Coombs, W.E.H. Stanner and Kim Beazley moved smoothly between prescriptions for the Pacific and for the Northern Territory.

Stanner, a veteran of the British Colonial Office in East Africa, was drawn into the Australian army’s policymaking unit for the South Pacific colonies during the Second World War.

During these years he became a confidante of several conservative politicians, and in 1953 Stanner was seconded by the Menzies government to the South Pacific Commission.

In The South Sea Islands in Transition (1953), funded by the Institute for Pacific Relation, he decried the colonial policy of the postwar Labor Government, for its ‘exaggerated emphasis on native welfare and development to the neglect of other legitimate interests.’

In the late 1950s, having finally secured an academic chair at ANU, Stanner would focus on Aboriginal studies. This eventually brought a return to Commonwealth service, with his appointment by Holt to the new Council for Aboriginal Affairs under Coombes.

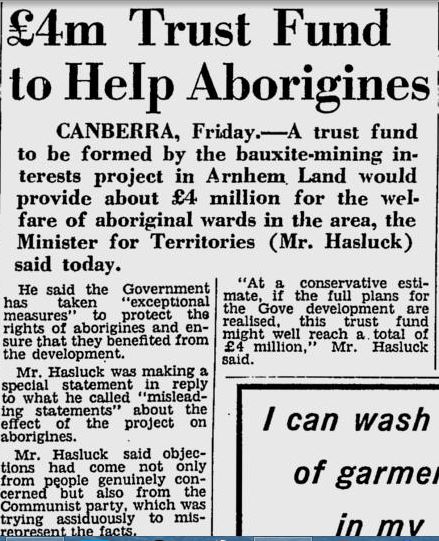

From the 1950s, Australian state managers sought to facilitate resource extraction by mining firms on Commonwealth Aboriginal Reserves and Crown land occupied largely by Indigenous people. (These and other commercial operations had hitherto been prohibited under the ‘protection’ regime.)

At the same time they paid obeisance to the welfare needs of the resident populations, members of which often lacked adequate clean water, sanitation, infrastructure and public service supplies, and who accordingly suffered very high disease incidence, infant and maternal mortality, low life expectancy, etc.

Thus the Aboriginal Benefits Trust Fund was created to receive royalties and make beneficial payments on behalf of residents of mining areas. As Minister for Territories, Hasluck was ‘the architect of linking indigenous property rights in land (then reserves) to income generated by that land.’

By the mid-1960s policymakers hit upon the idea of endowing property rights which would allow their holders to exercise a limited set of administrative powers. The form of title, however, ensured the Crown would retain all subsurface mineral ownership, and the land otherwise had little commercial value or stock of tangible assets.

Conferring incorporated entities with these ownership rights granted a stake in proceedings to a narrow stratum of ‘Indigenous representatives’ at the head of those bodies. Senior figures were assigned a measure of managerial autonomy. This included the right to negotiate, on behalf of the ‘community’, ‘informed consent’ deals with mining companies, to grant licences and commercial lease agreements (e.g. Indigenous Land Use Agreements and Native Title Agreements), and thus to strike rent-sharing contracts.

The latter channelled into trust funds a portion of revenue from mining operations. A large share of these payments (>40%) were allocated to administrative expenses (consultants, legal advice, operational budgets, etc.) which the organizations could be expected rationally to have maximized.

In 2010-11, for example, the Northern Land Council received a royalty-equivalent payment of $28 million from the Aboriginals Benefit Account (ABA) to cover administrative costs, and $9 million from the ABA for onward distribution to royalty associations. That financial year the Northern Land Council spent $2 million on consultants and $3.3 million on travel expenses. The Chief Executive Officer received total remuneration (including salary, spending allowance and performance bonus) of $172 000. The five other senior executives each received salaries of $126 000.

By accommodating the aspirations of ‘Indigenous leaders’ within the prevailing order (and by encouraging those individuals to seek advancement by virtue of their ethnic identity), state managers forestalled the prospect of social instability arising from political radicalization across ethnic and group boundaries.

Woodward’s original letters patent had directed him towards the ‘promotion of social harmony and stability within the wider Australian community by removing so far as possible, the legitimate cause of complaint of an important minority group within that community.’

While the common origin and simultaneous development of the Australian and PNG property regimes is rarely emphasized, their institutional resemblance has been noted.

Lately it has assumed particular prominence thanks to a growing chorus advocating the conversion of native title holdings into (or their extinguishment by) full private property.

This call has increasingly been issued by representatives of the Centre for Independent Studies, the Murdoch press, the Cape York Institute, former ALP president Warren Mundine, and other members of the former National Indigenous Council. The Commonwealth government’s ‘aggressive land tenure reform agenda’ (Kevin Rudd) lies behind its compulsory acquisition of land in the ongoing Northern Territory Emergency Response, and the moves to promote and enable Indigenous home ownership.

Participants in this ideological enterprise, especially the ANU economist Helen Hughes, have also directed fire at the customary property regime of Papua New Guinea.

In familiar arguments (which I noted in a recent post discussing agrarian property rights in sub-Saharan Africa), Hughes claims that productivity-raising investment in PNG agriculture is limited under the prevailing institutions of informal common property. These existing rules prohibit the transfer of land ownership to its most efficient user, prevent any agent from excluding other agents from capturing as private benefits the rewards to his or her private effort, and provide insecure tenure under which land can’t serve as collateral for borrowing.

Calls to displace customary property in PNG have sounded ever since reforms to land tenure were attached as a loan conditionality by the World Bank in 1995. (This led to riots which were repeated in 2001.) AusAID has devoted funds to this cause through its Pacific Land Mobilisation Program.

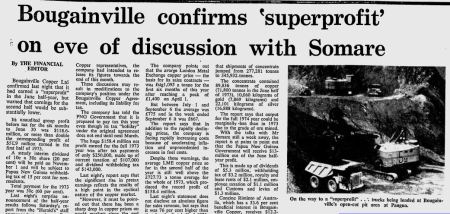

The project has advanced considerably via the National Land Development Program, launched by the Somare government in 2007. A ‘taskforce’ associated with this Program held a summit which issued the following declaration: ‘The dismal land policy that held sway in Papua New Guinea’s first thirty-four years of independence will soon be history.’ (The Aboriginal Australian lawyer Mick Dodson contributed to this summit, noting the simultaneous progression, in Australia, of a ‘debate concerning wealth creation on communally owned indigenous land.’)

In 2009 legislation was passed unanimously through the PNG national legislature, allowing Incorporated Land Groups to ‘deposit’ their property rights in a ‘central registry’, whence ‘productive land users… either from within or without the landowning social unit, access and utilise the land productively. In return, members of the customary landowning social unit derive incomes from availing their land.’

Thus group-based corporate property has been used as a stepping stone towards full privatization of land resources, and as a means of enrichment by functionaries holding elevated positions within the ILG hierarchy.

In Papua New Guinea there is open and trenchant criticism of the institution.

In a 2010 public event, the chief bureaucrat in the Department of Justice, Dr Lawrence Kalinoe, described how trustees of customary property colluded with logging firms and Land Department officials: ‘Officers and certain rogue landowners are colluding and conniving with each other to sell off customary land for their own benefit and interest while the majority of landowners are left out.’

In 2004, an official in the Department of Petroleum, Samuel Koyama (now employed as a advisor by ExxonMobil), published a paper which described how such behaviour was due not to the presence of a few rogues or bad apples, but arose inevitably from the principal-agent problems involved in incorporated entities whose senior officers are granted control rights over its ‘community’ assets.

In Australia, on the other hand, no such serious discussion of the policy goals of state managers with respect to Indigenous land rights and native title is ever undertaken.

There is little critical understanding of the property structure involved, and nobody mentions the obvious agency problems created by institutions such as land trusts and councils.

In the historical accounts allowed, via education and media, to impinge on popular consciousness, the Australian state’s recognition and enforcement of Indigenous ownership rights is supposed to have been compelled by the activism of pressure groups.

There is no acknowledgement that the ruling elite had independently formulated its own strategic objectives, and that ‘community trusteeship’ was initially a bipartisan elite project favoured by Cabinet ministers and high-level civil servants of all stripes.

Instead, ‘land rights’ and later native title are supposed to have resulted from moral suasion, the ‘threat point’ of embarrassment before the United Nations, and appeals to the better nature of the Australian judiciary and political class — alongside the latter’s gradual enlightenment and maturation with regard to racial questions.

All along, it is said, the common law held a place for Indigenous customary rights and the property title of traditional owners — though for 200 years this acknowledgement was stubbornly denied due to prejudice. Recognition and enforcement of these rights was sure to come eventually: it simply awaited the efforts of activists and the evaporation of wilful blindness.

With this origin myth surrounding the policy framework of land rights and native title, its social and political implications rarely receive adequate description or analysis.

Treatment of the subject by a conventional economist identifies what is at stake rather more clearly than does the standard legal exposition. But each version is narrowly focused and, in its own way, takes an apologetic view.

A group of right-wing economists, aligned with the Institute of Public Affairs think-tank, did attempt to analyze the High Court’s recognition of native title using the ‘law and economics’ theories of Richard Posner, for which evolution of the common law is supposed to promote efficiency (i.e. increase profits). They tested this hypothesis using the response of equity prices to judicial decisions and statutes extending Indigenous title. Having received inconclusive results, they declared themselves analytically defeated.

On the other hand, among ‘progressive’ left-liberal commentators, scholars and activists there is little concern or thought for questions about property relations. There is, however, much nostalgic Schwärmerei for the Whitlam and Keating ALP governments, and accordingly little critical understanding of policies implemented under those administrations.

The unquestioningly favourable opinion of progressives towards Indigenous land rights and native title is encouraged by the emergence, since the 1990s, of declarations of opposition to the policy made by conservative political parties and figureheads. The latter groups have led advocacy of a transition towards fuller private property.

The interpretative infirmity of left-liberals is compounded when, under the sway of nationalism and identity politics, such circles implicitly deny the existence of social or class divisions between members of the same ‘race’ (or, from the opposite direction, reject the idea that a commonality of interest unites members of a single class from different ethnic backgrounds).

What then are some implications of Australian native title and land rights?

Firstly, the recognition of group-based corporate land rights has very different consequences for ‘traditional owners’ in Australia from those in southwest Pacific countries. Legal ownership and economic ownership are not coextensive.

In the Melanesian case, untitled ‘customary’ property and registered land functions as a productive asset to which some ordinary people (direct producers) genuinely retain use rights. Possession of land (if not exclusive dominion) allows them to satisfy basic needs, undertake sustenance-drawing activities and secure personal livelihoods. Land serves as a subsistence base for producing food and other material goods, and as a source of cash income.

In Australia, on the other hand, most of those who hold land rights or native title are nonetheless reliant for their livelihoods on earning wage or salary incomes, on market exchange or on welfare provision or government subvention. Land for these people isn’t a productive asset contributing to their reproduction or subsistence; though it may be used to undertake hunting or fishing, these are mostly ceremonial or leisure practices.

What then of those individuals holding executive and administrative positions in trusts and other incorporated bodies? Together with consultants, lawyers, etc. (payment to whom makes up much of the administrative expenses of those entities), the remuneration of these people may be said to include extractive income or rent linked to property ownership. Their positions and social status derive entirely from enforcement of ownership claims.

In both the Australian and Melanesian cases, the incorporated entities (Land Groups and Land Councils or Land Trusts) hold property as agents or trustees of the customary owner (‘the community’). As with other forms of corporate property, whether a person has control rights (i.e. may exercise decision-making authority) in the asset depends on his hierarchical status in the bureaucracy. In this they resemble the assets managed by state bureaucracies and the Catholic Church during the Middle Ages (in which, though ownership was nominally assigned to an organization or entity, the only members who actually exercised these rights were those senior members of the hierarchy who held ‘the Power of the Keys’).

A few functionaries exercise administrative powers: negotiations and transactions with outside parties, receiving and disbursing net revenues generated by the asset, managing portfolios or engaging outside contractors to do so, making grants or loans, bestowing operating licences, etc. Senior officers often hold advisory positions with governments and consult for private firms.

When some agents are assigned, in this manner, a limited but exclusive set of control rights over a productive asset, and where no other party has the full complement of bourgeois ownership rights, those agents may be encouraged to push for appropriation of the ‘missing’ powers: transfer rights (to sell the asset to the highest bidder) and residual claimancy (the right to claim the net income generated by the asset after all fixed payments have been made).

Those agents may chafe (as has Indigenous Business Australia and its forerunners) at constraints applying to use of ‘their’ assets, such as the statutory obligation to take ‘community interests’ or social considerations into account, rather than simply maximizing profits. (Thus Soviet managers, having been granted ‘enterprise autonomy’ during the 1980s, had within a few years secured full privatization of state assets.)

These agents will receive external support for this project from those who seek to get their hands on currently inalienable property. These latter groups will engage spokespeople (like Helen Hughes) to clamour for more ‘well-defined’ property rights, i.e. dominium plenum.

This is one reason why recently, in various countries around the world, the registration as exclusive formal title of communal ‘customary property’ (e.g. the definition and enforcement of Indigenous land rights and native title) has given way almost immediately to its annulment, or to its extension into full alienable bourgeois property, or to lease arrangements with operators engaged in full-scale market activity.

Within a capitalist social order, inalienable corporate property is an unstable form of asset ownership.

It is an intermediate state of affairs between unowned open-access resources (res nullius) or state property, as the starting point, and full privatization as the desired terminus.

It is adopted by national governments and development agencies as an initial means of fixing rights to exclusion (i.e. assigning to a party exclusive rights of entry, use, management, enjoyment of fruits, etc.) in worldly things from which non-owners are not currently excluded.

The latter circumstance, at this point in history, exists only in a few dwindling parts of the globe. In these areas — due to remoteness, aridity, barrenness etc. — some domain, territory or resources has not been appropriated as exclusive property, because the costs of enforcing ownership exceed the stream of expected benefits (i.e the resource isn’t sufficiently valuable).

In these regions, consequently, a foraging, herding or low-productivity farming society continues to manage its hunting, pastoral or cultivated land, waters, forests, fisheries, etc. as open-access, communal or (occasionally) state land.

When the potential asset becomes more valuable (due e.g. to a mineral discovery or newfound suitability for production of a cash crop), but it is presently impossible for political or other reasons to assign and enforce parcels of individual property rights, then exclusive ownership rights may be allocated to (or defined for) a local community, resident group or other entity.

Thus Jim Fingleton, who as part of the Papua New Guinea Lands Department participated during the 1970s in land reforms, and who is a staunch defender of Incorporated Land Groups against their right-wing Australian critics, has rejected the description of customary tenure as ‘something like communism.’ Instead, he has said, it ‘should be seen as a form of private property rights, albeit that the rights are owned by a group rather than by individuals’.

From there the group may grant operating licences or lease out access to the asset (or grant some other kind of indefeasible claim of the type demanded by market participants), or gradually acquire the full bundle of private ownership rights, or (the bonds tying the original possessors to the resource having slowly been eroded by the ups and downs of commercial activity) the latter rights may eventually be acquired by some other party.

This is what lies behind the sudden contemporary discovery, by the likes of Elinor Ostrom and Thráinn Eggertsson, that ‘common property’ (i.e. exclusive group ownership) too can be an efficient (low-cost) way to govern natural resources, and should sensibly be encouraged in certain circumstances.

This line of research, suddenly all the rage, has been taken up by policymakers as part of the ideology accompanying enclosure (a.k.a ‘well-defined property rights). Ostrom applies a wrinkle to Hardin’s ‘tragedy of the commons’ article (1968), which privatization advocates milked for several decades’ worth of intellectual free kicks. What appears at first to be a posthumous pardon for ‘the commons’ actually involves the executioner dressing up in the corpse’s clothes, the better to evade detection.

For the recognition of group-based corporate land rights isn’t about efficiency, and is still less about equity, ‘custom’ or tradition. Like most institutional transitions, it is about control: a class or group’s attempt to advance its power and distributional claims.

The formalization of customary ‘land rights’, including Australian native title, should be understood as part of a broader historical process: the expansion of private ownership rights into new domains including retirement provision, the atmosphere, marine fisheries, river basins, higher education, charity, and whole regions of the world from which capitalist property relations were previously absent.

Tags: Aboriginal Australians, Australia, customary law, customary property, Fiji, imperialism, Indigenous Australians, Melanesia, nationalism, Native Title, Papua New Guinea

June 14, 2012 at 5:26 pm |

[…] assignment of new decision-making powers over large pools of assets to union bureaucrats and Indigenous ‘representatives’, restricting eligibility to previously universal welfare entitlements through means testing, […]

June 22, 2012 at 2:19 pm |

[…] and in remote or economically marginal regions like the Sahel, sub-Saharan Africa and the South West Pacific. These areas are occupied by small farmers, ‘garden’ cultivators, livestock herders and […]

June 25, 2012 at 2:36 pm |

[…] people into a political response based on ethnic identity, by granting administrative powers, limited property rights and other privileges to an Indigenous elite. This project involved bringing Indigenous people […]

February 13, 2013 at 9:50 am |

[…] The practice of government apologies was tied, but not necessarily so, to the awarding of monetary reparations, restitution of plundered goods or the recognition of group ownership of property. […]

March 31, 2013 at 10:11 pm |

[…] people into a political response based on ethnic identity, by granting administrative powers, limited property rights and other privileges to an Indigenous elite. This project involved bringing Indigenous people […]

April 8, 2013 at 7:22 pm |

[…] All political ‘movements’ that look to the bourgeois state for salvation thus ultimately become vehicles for rent-seeking. […]