On any reckoning, the Australian government’s militarized ‘border protection’ regime has now endured for over a decade. Initially viewed by journalists and decried by left-liberal critics as a mere electoral manoeuvre, to be extended or retracted according to the public mood or change of government, it has instead hardened into a permanent standing feature.

It has resisted disbanding or reform, despite widespread opposition and notable failure to achieve the ends publicly adduced for it. Maritime patrols have multiplied and detention camps become encrusted. How to explain their emergence and survival?

Most discussions neglect a crucial aspect. ‘Border protection’ is a kind of self-blockade, a barrier enforced by what the Royal Australian Navy calls a ‘Thick Grey Line’ of naval surface presence and surveillance. It is made possible, and appeals to Canberra, thanks to the recent spread of state jurisdiction over parts of international waters.

The latter development, which has allowed ‘privatization of the oceans’ and extension of ‘national security’ bailiwicks, was described in the previous post.

How exactly have legal arcana about fisheries management, by swelling Canberra’s maritime jurisdiction, led to the Australian government’s ‘new regime’?

- Since the 1970s, the acquisition by states of limited jurisdiction and exclusive economic rights over adjacent coastal waters and extended continental shelves has meant growth in that portion of the world’s territory in which states can (practically speaking) restrict the movement of people.Non-nationals have kept legal rights to innocent passage through these (international) waters, and vessels there remain under flag-state law.But coastal states have gained implicit authority to regulate almost every other activity — including transit with the aim of arriving in a country to seek refuge there. (The explicit authority to prevent and punish infringement of domestic immigration laws begins outside a state’s territorial sea, in its contiguous zone.)

This has implied a paring back of the right to seek asylum from persecution.

This right had always, from the beginning, been heavily circumscribed and sparingly awarded, and was trumped whenever it was held to conflict with any other prerogative. The provisions of refugee law, according to one Australia High Court judge, do not impose any ‘limitation upon the absolute right of member States to regulate immigration by conferring privileges upon individuals… [No] individual, including those seeking asylum, may assert a right to enter the territory of a State of which that individual is not a national.’

‘Border protection’ policies have thus been a predictable result of circumstances in which the free movement of people conflicts with the sovereign right of states to determine who may enter and remain within their territorial borders — and in which state jurisdiction has been extended into places where it didn’t previously apply.

Creation of exclusive economic zones (EEZs) has endowed states with maritime interests of high strategic worth. These naturally have become matters of ‘national security’, to be preserved if necessary by the armed forces.

Within their respective EEZs, states have been obliged to place their coercive instruments at the service of locally owned firms, to pursue and protect these firms’ property claims in assets (fisheries, offshore oil and gas reserves, elevated platforms, drilling rigs, etc.) against interference, encroachment, seizure, expropriation or unilateral transfer of ownership.

This has licensed states to undertake enforcement measures within maritime zones: patrols, emplacement of sensors, surveillance, reconnaissance, interception, forced boarding, detention and confiscation of vessels, declaration of ‘exclusion zones,’ declaring approved sealanes, etc.

No dramatic leap of logic or political principle has been involved, therefore, when it has been declared that EEZs, contiguous zones and territorial waters, those beleaguered redoubts of ‘national sovereignty’, should also be protected against ‘unauthorized maritime arrivals’.

- Nonetheless the much-stated need to protect Australia’s vulnerable maritime approaches against ‘boat people’ has been a pretext which state leaders have deliberately used to pursue Canberra’s strategic objectives. In August 2001 the National Security Committee of Cabinet discussed how to establish a ‘deep offshore’ continuous presence that would allow the ADF to undertake what the prime minister called ‘naval blockade of the Indian Ocean’.

I’ll say a little more about the implications of this first point towards the end of this post, but will explain the second point firstly.

In 2004 Canberra announced creation of a Joint Offshore Protection Command (now Border Protection Command) comprising ADF and Customs personnel. It would be responsible for Operation Resolute, a joint patrol of Australia’s EEZ.

The Navy website for this program boasts that its ‘Area of Operations covers approximately 10% of the world’s surface.’

Along with these operations — centred on the energy-rich Timor Sea and the northwest coast abutting the Indian Ocean, off the Pilbara and Kimberley — the BPC was to oversee a Maritime Identification Zone.

The latter would cover all vessels passing within 1000 nautical miles of Australian coastline. It would oblige all vessels seeking to enter Australian ports, as well as those merely having strayed inside the Australian EEZ, to provide Australian authorities with information regarding location, speed, crew, cargo and course of transit.

International law provided no basis for imposing such requirements on foreign-flag vessels. The area involved stretched into the territorial waters of Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, East Timor, New Zealand and New Caledonia.

The strategic considerations underlying such policies are pointed to in the ADF’s 2012 force posture review. Canberra’s military planners note that, amid shifts in the ‘Asia-Pacific strategic balance and great power competition’, including Washington’s regional ‘pivot’, Australian forces must be prepared to take part in ‘coalition operations in the wider Asia-Pacific.’

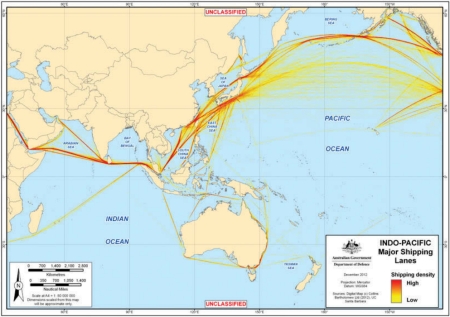

They note that ‘securing sea lines of communication and energy supplies will be a strategic driver for both competition and cooperation in the Indian Ocean region to 2030, and Australia’s defence posture will need to place greater emphasis on the Indian Ocean, as indicated in the 2009 Defence White Paper.’

Defence Minister Stephen Smith spoke of developing a ‘force posture that can better support operations in our northern and western approaches, as well as operations with our partners in the wider Asia Pacific region and the Indian Ocean Rim.’

And what might such joint operations be?

In 2010, military strategists from the US Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments presented Pentagon planners with a ‘candidate’ air-sea battle campaign for use in ‘potential conflicts involving China that could arise in the Western Pacific.’

In the envisioned theatre-wide combat, US naval forces would focus on ‘high-priority’ anti-submarine, anti-surface, anti-missile warfare and area denial in the East China and South China seas.

Washington would depend on allies (with Japanese and Australian forces foremost) to engage in ‘distant blockade’ and interdiction against China-bound seaborne trade:

In the event of a protracted conflict, choking off Chinese seaborne commerce to the maximum extent possible would likely be preferred to conducting large-scale operations in China itself.

US and allied forces ‘could exploit the Western Pacific’s geography, which effectively channelizes Chinese merchant traffic’:

Traffic bound for China would be intercepted as it tried to enter the southern portions of the South China Sea, i.e., beyond range of most PLA A2/AD systems, from the Malacca, Singapore, or major Indonesia straits…

Australian and other allied forces would thus have three key tasks:

-

-

-

-

- Securing “rear areas” by neutralizing any PLA units forward-deployed to such areas;

- Establishing a “distant blockade” to interrupt Chinese seaborne commerce; and

- Cutting off or seizing Chinese offshore energy infrastructure.

-

-

-

Australian equipment and personnel would be useful for such maritime interception operations ‘since they generally would not involve major combat, allied aircraft and ships too vulnerable for employment against the PLA’s A2/AD battle network… These forces would patrol key chokepoints in Southeast Asia as the central element in a distant blockade’:

Lastly, “distant blockade” operations could also require two additional operations: disrupting Chinese undersea telecommunications lines; and seizing or destroying of Chinese undersea energy infrastructure and/or disrupting undersea energy flows to China.

Carrying Out Peripheral Operations to Secure “Rear Areas”

Over the past several years, China has helped develop port facilities in places like Gwadar (Pakistan), Chittagong (Bangladesh), and Sittwe (Burma) that could be used for military purposes. It recently deployed naval forces off Somalia in conjunction with anti-piracy operations for the first time, and PLA officials have floated trial balloons about acquiring access to forward bases. It continues to wage vigorous “dollar diplomacy” with various statelets in Oceania that could eventually translate into access to facilities for military purposes. In short, China appears to be developing options for creating a network of overseas military bases stretching from Africa to Oceania. Such presence would be consistent with the actions of many other rising powers throughout history; however, it could have serious implications for the military balance and consequently for US security and the security of its allies.

Preserving a stable military balance under these conditions would necessarily require the United States and its allies to maintain the capability to neutralize PLA bases outside the Western Pacific. This would involve removing the threat of diversionary PLA operations.

Such peripheral operations could take some time to complete, given the large distances between theaters of operation. Still, the United States and its allies would enjoy two important advantages. First, assuming the US fleet controls the seas, allied forces could take the lead in many of these peripheral operations, with US forces in support. For example, Australia is the most powerful state near Oceania, and has highly capable military forces that could conduct operations to neutralize any small PLA forces in the region.

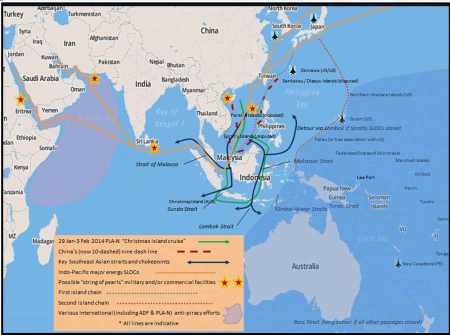

Thus Canberra’s strategic focus has, since the 1990s, been on establishing its military capacity for sea control and power projection in nearby regional straits (several of them key global maritime chokepoints) and on countering Beijing’s so-called ‘string of pearls‘.

Strategists such as Ross Babbage (in 1988) have noted the convenient placement, for this purpose, of Australia’s Indian Ocean External Territories:

Christmas and the Cocos Islands could serve as convenient forward refuelling and staging points for aircraft and ships in the north-western approaches… [Access] to these territories would also extend Australia’s reach into the surrounding region for surveillance, air defence and maritime and ground strike operations. The islands could, in effect, serve as unsinkable aircraft carriers and resupply ships.

For public consumption, politicians cite the geographic location of Australian offshore oil and gas reserves and the proximity of ‘failed states’.

Refugee boat arrivals to the Cocos Islands, Ashmore and Cartier Islands and Christmas Island also provide a useful pretext for militarizing the portions of the Indian Ocean, Timor Sea, Arafura Sea and Coral Sea that fall within the Australian EEZ.

The transit of ‘boat people’ has granted Australian authorities a convenient and plausible reason to undertake patrols and inspections, place sensors, conduct surveillance and reconnaissance, engage in interception and forced boarding, detain crews and seize vessels in these areas.

Meanwhile the ‘fine strategic location’ of Australian offshore detention facilities in the Admiralty Islands and Nauru is apparent from a ‘cursory glance at a map of the Pacific’, or some acquaintance with naval history.

Of course, Australia’s state leadership does not spell out publicly, before a mass audience, its strategic goals and its tactics for meeting them.

Nonetheless it sometimes, for various reasons, finds it necessary or expeditious to allow certain matters to appear, through reliable media conduits, ‘in front of the children’, if only to rouse electorates in their support.

One of the basic tasks of electoral politics (and its satellites in the media and academic worlds) is to mobilize and harness a mass constituency behind narrow elite objectives. In the present context, stoking of anti-refugee attitudes, among its other benefits, allows such a happy convergence of popular feeling with ruling-class aims.

Left-liberal critics of ‘border protection’ policies attribute their introduction to ‘perennial’ Australian popular chauvinism and anti-immigrant racism. In reality, public attitudes on such matters have no existence outside of their shaping by professional opinion makers, and exercise no independent influence on the initiation of state policy.

Mass opinion, and particularly that of ‘activist’ groups, may nonetheless provide a useful tool or lever for achieving elite objectives, when the latter conflict with goals held by the ruling elite of another state.

Thus the respectably ‘progressive’ concern for threatened whales and endangered southern bluefin tuna may help satisfy Canberra’s strategic purposes, in another region mentioned in the ADF’s recent force-posture review:

Increased pressure on resources may see interest in engagement in the Antarctic continent… Increased resources for relevant agencies, not just Defence, will be necessary to strengthen Australia’s presence in Antarctica and the Southern Ocean in the face of likely future challenges.

Or consider Australian 1999 military intervention in Timor-Leste, which various activist groups conceived as supporting local ‘self-determination’, and thus worthy of salute. This operation (repeated in 2006) secured maritime control over the deepwater Ombai-Wetar Straits, a vital avenue off the northern Timor coast for US submarines passing between the West Pacific (and East Asia) and the Indian Ocean.

The East Timor matter illustrates what concerns lie behind Canberra’s attitude to maritime law and seaborne traffic.

In 1973 the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea convened in New York, with US delegates holding the following strategic priorities:

Because of dependence on oil and other resources, and the need of the military to pass through and over straits and in zones of economic jurisdiction, one of the primary security objectives of the United States may become the achievement of working relationships with coastal developing states.

The U.S. Government maintains that the invulnerability of its nuclear missile submarines depends on their ability to pass through international straits submerged and unannounced. International agreement on a 12-mile territorial sea would place dozens of international straits under the “innocent passage” regime of the territorial sea unless the demands of maritime states for unimpeded passage are agreed upon. (The legal regime of “innocent passage” permits transit by all ships except those which threaten the peace, good order or security of the coastal state. The lack of a more precise definition has left coastal states in a position to determine for themselves what is or is not “innocent passage.”)

Five international straits have been identified as essential for passage by U.S. missile submarines: Gibraltar, Malacca, Lombok, Sunda and Ombai-Wetar. Two of these are too shallow for underwater passage, the other three are controlled by states with which the United States maintains good relations and working modus vivendi, and which have and probably will continue to permit passage for submerged U.S. submarines.

[…]

The navy has been concerned that the breadth of the continental shelf under national jurisdiction might limit the freedom of the United States to place listening devices off the shores of foreign countries.

[…]

In addition to the questions of transit through straits and submarine tracking, a third strategic concern is that zones of extended coastal state jurisdiction will curtail conventional naval operations.

It was declared ‘essential’ for the passage of US ballistic missile submarines between the Western Pacific (and Northeast Asia) and Indian Ocean that these straits be ‘controlled by states with which the United States maintains good relations and working modus vivendi, and which have and probably will continue to permit passage for submerged U.S. submarines’:

The two Indonesian straits, Lombok and Ombai-Wetar, might be closed to unannounced underwater passage of U.S. SSBNs in any case because according to Indonesia’s interpretation of the archipelago principle of enclosed waters, they are considered internal rather than international waters.

On the other hand, the United States seems to have a working arrangement with Indonesia for passage of SSBNs through its straits though the Indonesian government has argued that the archipelago principle does not infringe on innocent passage, it requires prior notification of transit by foreign warships and has raised questions about the innocence of supertanker passage because of the danger of pollution.

In spite of Indonesian jurisdictional claims, the United States maintains that the Indonesian straits are international. According to press accounts and Indonesian sources, however, the United States routinely provides prior notification of transit by surface ships and presumably (if only as a practical convenience) relies on some special bilateral navy-to-navy arrangement for submerged passage, consistent with the requirements of concealing the details of SSBN passage from foreign intelligence.

Although this modus vivendi is rather contingent, it satisfies America’s needs as long as an Indonesian government as friendly as that of Suharto is in power.

Such concerns were impressed upon the Australian prime minister, visiting Washington in 1976 after Jakarta had annexed East Timor. The Fraser government’s negotiating position at UNCLOS dutifully aimed to ‘bridge the differences’ between the United States and smaller littoral and archipelagic states.

And, with that, I’ll now finish this post by returning to the first point mentioned at its beginning.

The gradual postwar development of the international law of the sea (culminating in the 1982 UNCLOS), under which states have extended jurisdiction into their adjacent coastal waters, took place during the same decades as codification of international refugee law. As long ago as 1930, at the League of Nations Conference for the Codification of International Law held in The Hague, delegates addressed the issues of territorial seas and nationality laws.

This historical coincidence does not imply complementarity. People’s right to free movement conflicts with the territorial sovereignty of states, and with the latter’s jurisdiction over borders and immigration. The first right retreats when the other privilege is advanced, just as personal (citizen) rights and property rights generally move inversely.

In recent decades, the acknowledged right of individuals to seek asylum from persecution has been limited and rolled back by governing elites worldwide. Political leaders have each asserted their state’s pre-eminent authority to control who may enter and remain within the territories over which it holds jurisdiction. (From this follows matters such as the incarceration of asylum seekers during the ‘process’ of status determination.)

The notorious 2001 assertion by the Australian Prime Minister — ’We will decide who comes to this country and the circumstances in which they come’ — expressed both a positive fact and a normative position: the state has sovereign authority over its territorial borders, and can set limits to migration flows.

Though a chorus of left-liberal groups and bien-pensant commentators shrieked at Howard’s words, none of them ever voiced a fundamental objection to the notion that a state has the sovereign right to determine who can enter and remain within its territory, and can set restrictions on numbers and categories of immigrants.

Seeking to make the best of this principle, rather than rejecting it, these ‘progressive’ voices merely plead that the state’s decisions (on refugees and immigration) should be made in more ‘humane’ fashion. (Thus the Australian Greens have repeatedly insisted that an increase in Australia’s ‘humanitarian program’ for refugees and family reunions should be balanced by a reduction in the intake of ‘skilled’ migrants, whom they have described as ‘queue jumpers’.)

Similarly, as described in the previous post, the Greens and associated conservationist groups uphold Canberra’s contested jurisdiction over portions of international waters (e.g. Australia’s Antarctic EEZ). They merely suggest that this control could be exercised better, e.g. total allowable catch of various fish species should be set at a ‘sustainable’ level.

On the other hand, the principled position — for socialists and for even minimally ‘left-wing’ people — is that the world’s oceans and their resources are not susceptible of appropriation by any state or private party — and that territorial states are not entitled, by virtue of their jurisdictional claims, to restrict the free movement of people (whether that movement involves flight from imperial violence, national dismemberment and state breakdown, or the pursuit, in a world of wage differentials between regions of varying levels of development, of a decent life in a country with jobs, roads, schools and sanitation).